Khalistan had become a thing of the past after India trudged on from the grisly period of peaking insurgency in Punjab, the assassination of a powerful Prime Minister, and the anti-Sikh riots that followed.

But certain occurrences in the past few months hint at the unearthing of a buried hatchet. In the light of these developments, an understanding of the evolution, dissolution and reappearance of the movement is called for.

Historical roots

The Khalistan movement started out as a Sikh separatist movement with the intention to carve out a Sikh homeland by way of establishing a sovereign state called Khalistan, meaning the ‘Land of the Khalsa’, in the Punjab region that includes both India and Pakistan.

‘Khalsa’ is a common term of reference for the community that adheres to Sikhism as a faith and also a special group of initiated Sikhs. The word means (to be) pure, clear, or free from. The Khalsa tradition was introduced by Guru Gobind Singh, the 10th Guru, in 1699, after his father, Guru Tegh Bahadur, was beheaded in the reign of Aurangzeb.

The establishment of Khalsa order gave a fresh orientation to Sikhism with a new system of leadership and gave a political and religious vision for the Sikh community. A Khalsa was then initiated as a warrior to protect people from Islamic religious persecution.

Fast forward to modern age, the idea of a separate Sikh homeland took shape during the fall of the British empire. It was in 1940 when for the first time, an explicit call for Khalistan was made in a pamphlet by the same name.

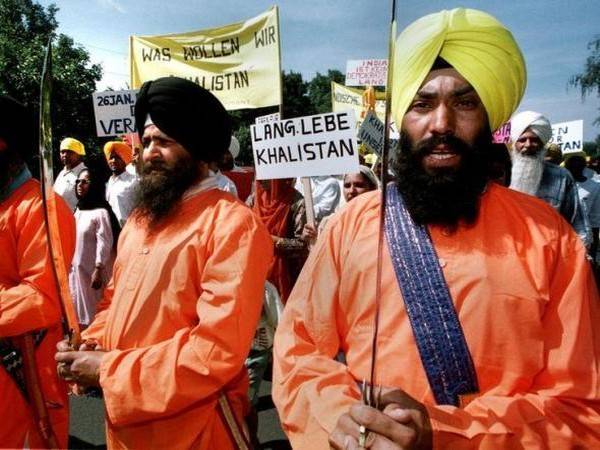

With the political and financial support of the Sikh diaspora, the movement for Khalistan began to gather momentum in Punjab. It continued through the 1970s and reached its pinnacle in the late 1980s as a separatist movement.

The territorial ambitions of Khalistan have since then expanded to include Chandigarh and much of northern India and parts of western India.

Jagjit Singh Chohan is the discredited founder of the Khalistan movement. Initially a dentist, Chohan was first elected to the Punjab Assembly in 1967. He went on to become the finance minister, but in 1969, he lost the Assembly election.

Building an overseas base

Following his electoral debacle, Chohan moved to Britain in 1969, and began campaigning for Khalistan to be created. In 1971, he went to Nankana Sahib in Pakistan and attempted to set up a Sikh government.

Yahaya Khan, the military dictator of Pakistan, proclaimed Chohan a Sikh leader; he was handed over certain Sikh relics which he took with him to Britain. These relics helped Chohan consolidate support and followers. Subsequently, he visited US upon the invitation of his supporters in the Sikh diaspora.

On October 13, 1971, The New York Times carried a paid ad claiming an independent Sikh state. This ad of Chohan enabled him to gather huge funds from the overseas community.

Towards the end of 1970s, Chohan was associated with the diplomatic mission in Pakistan which aimed to encourage Sikh youth to travel to Pakistan for pilgrimage and indoctrination for separatist propaganda.

Chohan maintained that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, had assured him all assistance in creating Khalistan after the 1971 Indo-Pak war.

Chohan returned to India in 1977, and then travelled to Britain in 1979, and established the Khalistan National Council. The contacts with various groups in Canada, the US and Germany were maintained and Chohan visited Pakistan as a state guest.

On April 12, 1980, Chohan formally announced the formation of the ‘National Council of Khalistan’ at Anandpur Sahib, and declared himself its president. Balbir Singh Sandhu was its Secretary General.

A month later, Chohan travelled to London and proclaimed the formation of Khalistan. Sandhu made a similar announcement in Amritsar.

Eventually, Chohan proclaimed himself the president of the ‘Republic of Khalistan’, set up a Cabinet, and issued Khalistan passports, stamps, and currency (Khalistan dollars).

On June 12, 1984, Chohan was interviewed by the BBC in London.

When asked “Do you actually want to see the downfall of Mrs Gandhi’s government?”, Chohan had asserted, “Within a few days, you will have the news that Mrs Gandhi and her family have been beheaded. That is what Sikhs will do.”

The Margaret Thatcher government in Britain then put a check on Chohan’s activities after this proclamation.

On June 13, 1984, Chohan announced a government in exile, and on October 31, 1984, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated.

In 1989, Chohan hoisted the flag of Khalistan at the Anandpur Sahib gurdwara in Punjab. On April 24, 1989, his Indian passport was deemed invalid and India protested when he was allowed to enter the US with a cancelled Indian passport.

Mellowing down of the radicals

Chohan gradually appeared to soften his stance and supported India’s attempts to defuse the tension by accepting surrenders by militants. However, the sister organisations in Britain and North America remained devoted to the cause of Khalistan.

In June 2001, after 21 years of exile, Chohan was permitted to return to India after he was granted pardon by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government.

Although the government chose to overlook his history of militant pursuits, upon his return, he said in an interview that he would keep the Khalistan movement alive democratically and underlined that he was always against violence.

In 2002, he founded a political party by the name of Khalsa Raj Party and became its president. The aim of this party was admittedly to continue his campaign for Khalistan. However, this notion was no longer attractive to the new generation of Sikhs.

Chohan largely retired from public life in his later years and passed away on April 4, 2007, after a heart attack at the age of 78. With his demise, the Khalistan movement also petered out.

The end of insurgency

The insurgency tapered off in the 1990s and the movement failed owing to several factors, primarily heavy police crackdown on separatists, factional infighting, and disenchantment from the Sikh population.

With annual demonstrations for those killed during Operation Blue Star, there remain traces of some support within India and the Sikh diaspora.

In the light of the recent developments, questions have been raised regarding the resurrection of the notion of Khalistan.

In early 2018, the police had apprehended some militant groups in Punjab. Then Chief Minister Amarinder Singh had remarked that the extremism was backed by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence and Khalistani sympathisers in Canada, Italy and the UK.

Khalistan rears up its ugly head

It was reported in February this year that Pro-Khalistan groups like the proscribed Sikhs for Justice (SFJ) have been trying to rake up sentiments and revive the movement in Punjab.

Expressions of anti-India sentiments from Canada are no secret, but India’s big security concern lately has been this outfit which has a strong virtual presence and is able to radicalise a good number people to rebel against the government of India.

An NIA team reached Canada last November, to probe the funding channels of pro-Khalistan groups which can contribute to unrest in India. Reportedly, over one lakh USD was collected in the name of farmers’ protests, as cited by officials.

On May 5, Haryana Police apprehended four people at a toll plaza in Karnal carrying three IEDs weighing 2.5 kg each.

On May 8, flags of Khalistan were found affixed to the main entrance of the Himachal Pradesh Assembly complex in Dharamsala. Himachal Pradesh Police booked SFJ leader Gurpatwant Singh Pannun under UAPA and sealed the state’s borders and beefed up security in the state citing pro-Khalistan activities.

The outfit’s announcement of a Khalistan referendum day on June 6 has also been banned.

On May 9, a Pakistan-made rocket-propelled grenade explosion was reported from the Punjab Police Intelligence headquarters in Mohali, just a day after the state police seized an IED loaded with RDX from Punjab’s Tarn Taran district.

These attacks happened after a communal rift between certain Sikh and Hindu groups in Patiala on April 29, setting off an alarm pertaining to security concerns.

These developments gravely point to efforts of Khalistani elements to sow seeds of distrusts in India, and this is a concern niggling at India’s security.

ALSO READ: UK Sikhs turning their back on Khalistan propaganda

Leave a Reply