While the international community is increasingly recognising the severe abuses perpetrated against the vulnerable Uyghur population, existing legal frameworks are inadequate due to the intricate nature of manufacturing processes and the lack of transparency surrounding them….reports Asian Lite News

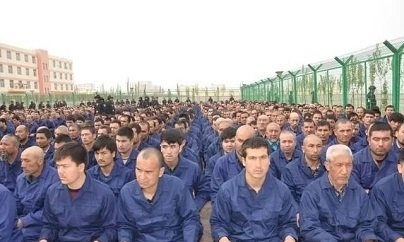

Over the last ten years, the global community and media have persistently highlighted the extensive atrocities inflicted by China upon its minority groups, particularly the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang province. The Uyghurs represent approximately 45 per cent of the region’s demographic and have endured various forms of oppression, including mass detainment and indoctrination through what are termed ‘vocational education and training centres’.

This has been accompanied by pervasive surveillance technologies, enforced sterilization, and systematic sexual abuse. In August 2022, Michelle Bachelet, the then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, released a significant report indicating that China’s treatment of the Uyghurs might amount to “crimes against humanity”.

The report detailed large-scale arbitrary detentions, torture methods such as forced starvation and coerced medical procedures, alongside evidence of forced labour.

The so-called ‘re-education camps,’ which have also been referred to as ‘internment camps’ or ‘concentration camps’ by various observers, first emerged in 2014 and saw substantial expansion in 2017. According to the Chinese government’s narrative, these actions are framed as necessary measures to combat terrorism, extremism, and separatism.

In 2019, claims made by the governor of Xinjiang suggested that many individuals had ‘graduated’ from these centres, leading to perceptions that numerous facilities had been shut down.

However, in 2020, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute revealed that this closure was merely a façade for a shift towards utilising the formal prison system for detaining those deemed a ‘threat’ to state security, evidenced by a marked increase in prosecutions and convictions of Uyghurs.

Furthermore, to evade international scrutiny, China has been employing deceptive strategies to suppress its Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang. One such tactic involves presenting forced labour as a labour transfer initiative aimed at employment generation, industrial development, and poverty alleviation.

Adrian Zenz, a prominent researcher on China’s policies in Xinjiang, examined the work practices of Uyghur Muslims in 2023 and uncovered that the labour-transfer programme involved the forced relocation of Uyghur Muslims to state-assigned jobs far from their home regions.

Unsurprisingly, these workers are threatened with prosecution or imprisonment should they attempt to leave their employment. Zenz asserted that this labour-transfer initiative is utilised in the production of various goods, including cotton, tomatoes and tomato products, peppers and seasonal agricultural items, seafood, polysilicon for solar panels, lithium for electric vehicle batteries, and aluminium for batteries, vehicle bodies, and wheels.

Another method through which China compels Uyghur Muslims into involuntary labour is via the prison system. As previously noted, recent years have seen alarming rates of Uyghur prosecutions. For example, Human Rights Watch reported that approximately half a million individuals in Xinjiang were prosecuted between 2017 and 2022.

Similarly, a leading media outlet disclosed that one county in Xinjiang recorded that one in every 25 residents was convicted on terrorism-related charges, all of whom were Uyghurs.

The accusations brought against Uyghurs by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) can range from serious charges like terrorism to trivial ones such as ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble.’ Given that labour is a standard practice for inmates, Uyghur Muslim prisoners are exploited to support China’s industrial growth by working in agriculture, mining, and the manufacturing of goods.

The troubling reports of forced labour in Xinjiang have prompted Western governments to implement legal restrictions on imports from the region.

In 2021, US President Joe Biden enacted the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act, requiring companies to prove that their imports are not produced through forced labour involving Uyghurs. Similarly, in April 2024, the European Parliament approved legislation set to take effect in 2027 that will screen imports linked to forced labour.

Notably, by the end of the first four months of this year, the EU had already imported goods valued at $641 million from Xinjiang. According to a 2022 study, polysilicon produced in Xinjiang, essential for solar panels, accounted for approximately 95 per cent of photovoltaic energy in the world’s top 30 solar power-producing nations.

The same research indicated that Xinjiang was responsible for about 18 per cent of globally traded processed tomato products and that one in five garments worldwide contained cotton sourced from the province.

Companies face significant challenges in identifying products made with Uyghur forced labour due to China’s strategic obfuscation of these practices under various pretenses, including the so-called labour transfer scheme.

Earlier this year, Human Rights Watch published a report condemning major global automotive manufacturers, including General Motors, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Tesla, for failing to adhere to responsible sourcing standards regarding aluminium linked to Uyghur forced labour in Xinjiang.

Recently, China has established itself as a leading producer and exporter of automobiles, with Xinjiang emerging as an industrial centre that experienced a dramatic increase in aluminium production, rising from one million tonnes in 2010 to six million tonnes in 2022.

Approximately 9 per cent of the global aluminium supply is sourced from Xinjiang, and since much of this aluminium is blended with other metals to create finished products, it becomes exceedingly difficult to ascertain the extent to which forced labour contributes to these goods.

While the international community is increasingly recognising the severe abuses perpetrated by China against the vulnerable Uyghur population, existing legal frameworks are inadequate due to the intricate nature of manufacturing processes and the lack of transparency surrounding them. Consequently, persistent pressure must be exerted on China to urge a change in its practices and to halt the dehumanisation, persecution, and exploitation of Uyghur Muslims.

ALSO READ: Tibetan leaders seek united stand on China from Biden, Modi

ALSO READ: China to ‘gradually resume’ importing Japanese seafood

Leave a Reply