At the Haripura Congress, Subhas Bose became president of the Congress and a year later in Tripuri, he forced the issue again despite strident opposition from the trio and won the Presidency by 95 votes more than Gandhiji’s candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya….reports Asian Lite News

Even as the PM installed the Subhas Chandra Bose hologram on his 125th birth anniversary, as part of his continued appropriation as a freedom movement icon in the magnum opus of throwing into stark relief Netaji’s persona, the tower of babble over his role went into overdrive.

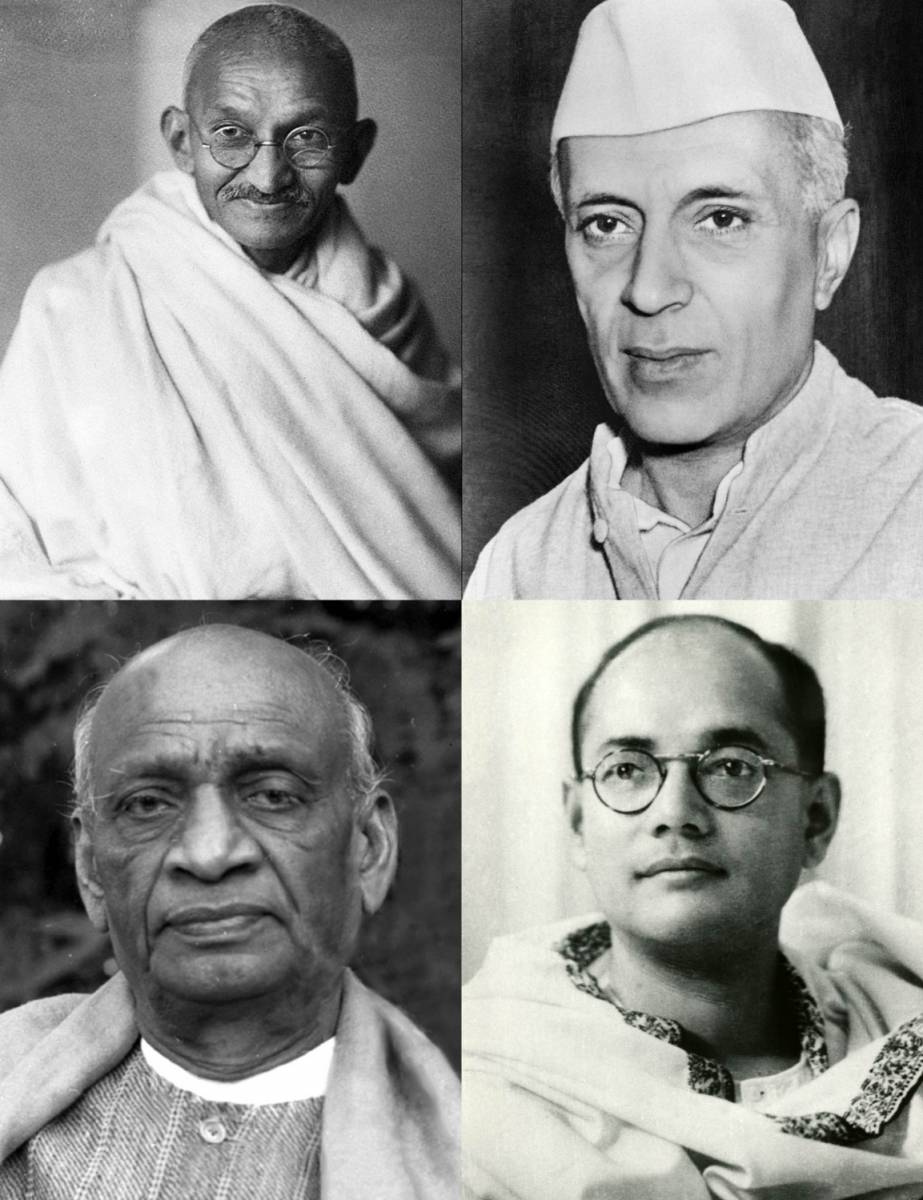

There are some important data points in history which need to be factored into his exact positioning amongst the Congress Big Four – Gandhiji, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel and Bose. Since superficiality and vacuousness are the order of the day, institutional memory needs to be given a booster dose so that things are put in the right perspective. In many ways, 1938 and 1939 were the moment of truth in a large number of Indian Princely States as powerful people’s movements flourished against the high handedness of the Ruling dispensation which directly drew its strength from the Paramount Power in the Princely States.

The challenge to the troika of Gandhiji, Nehru and Patel also came around the same time. At the Haripura Congress, Subhas Bose became president of the Congress and a year later in Tripuri, he forced the issue again despite strident opposition from the trio and won the Presidency by 95 votes more than Gandhiji’s candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya. After Bose won convincingly, Gandhi said Pattabhi’s defeat was “more mine than his”.

At Tripuri in March 1939, GB Pant moved a resolution asking Bose to appoint a Working Committee in line with Gandhi’s ideas. Bose in a passionate presidential address on March 10, 1939, where very specifically focusing on the Princely States, his opinion coalesced with Nehru, stated, “But since Haripura much has happened. Today we find that the Paramount Power is in league with the State authorities in most places. In such circumstances, should we of the Congress not draw closer to the people of the States? I have no doubt in my own mind as to what our duty is today. Besides lifting the above ban, the work of guiding the popular movements in the States for Civil Liberty and Responsible Government should be conducted by the Working Committee on a comprehensive and systematic basis. The work so far done has been of a piecemeal nature and there has hardly been any system or plan behind it. But the time has come when the Working Committee should assume this responsibility and discharge it in a comprehensive and systematic way and, if necessary, appoint a special sub-committee for the purpose.”

At the session proper, Bose fell very ill and was bed ridden. The Presidential election was dramatic and certainly unlike previous humdrum ones. The election was followed by sensational developments culminating in the resignation of twelve out of fifteen members of the Working Committee, headed by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Dr Rajendra Prasad. Another distinguished member of the Working Committee, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, though he did not formally resign, issued a statement which led everybody to believe that he had also resigned. On the eve of the Tripuri Congress, events at Rajkot forced Mahatma Gandhi to undertake a vow of fast unto death. Gandhi chose not to travel to Tripuri and instead deliberately went to Rajkot.

The Congress closed ranks against Bose and the best description of what transpired at the fabled session came from Bose’s brother Sarat Bose’s sharply written letter to Gandhiji on March 21, 1939. It was a scathing fulmination:

What I saw and heard at Tripuri during the seven days I was there, was an eye opener to me. The exhibition of truth and non violence that I saw in persons whom the public look upon as your disciples (targeting Nehru, Patel, Azad and company) and representatives has to use your own words, ‘stunk in my nostrils’. The election of Subhas was not a defeat for yourself, but of the high command of which Sardar Patel is the shining light. The propaganda that was carried on by them against the Rashtrapati and those who happen to share his political views was thoroughly mean, malicious and indicative and utterly devoid of even the semblance of truth and non-violence. At Tripuri, those who swear by you in public offered nothing but obstruction and for gaining their end, took the fullest and meanest advantage of Subhas’s illness. Some ex members of the Working Committee went to the length of carrying on an insidious and incessant propaganda that the Rashtrapati’s illness was a ‘fake’, and was only a political illness.

The letter was a denouement of the Congress and the way it had treated Subhas Bose. At Gandhiji’s insistence, Sardar responded to Sarat Bose’s letter where he went onto politely dismiss all the charges levelled by Sarat Bose. All this finally culminated over time in Subhas Bose being disqualified by the Working Committee as the president of the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee.

Bose split from the Congress and started the Forward Bloc in opposition to the Congress. Narahari D. Parikh in Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel writes that, “Although throughout this period the dispute was between the Working Committee and Subhas Bose, he and his followers blamed the Sardar for everything who was the main target of their wrath. For this the real reason was the Sardar’s forthright manner — for he spoke frankly and bluntly and never learnt the art of pleasing anyone by sweet words.”

In his letter to Jawaharlal Nehru on August 28, 1939, Netaji complained, “If the old guard wanted to fight why did they not do so in a straightforward manner? Why did they bring Mahatma Gandhi between us?”

On April 4, 1939 Sarat Chandra Bose had written to Nehru along the same lines, “I believe I shall not be unjust if I say that the members of the Working Committee would have shown greater courage and straightforwardness if they had decided to act on their own and not used Mahatmaji as their cover. Their plain duty was to keep Mahatmaji above all controversy as he should be in our political life.”

Both missives slammed Gandhi’s followers like Sardar Patel, Bhulabhai Desai etc. Bose wrote about this painful experience in his essay “My strange Illness”.

Patel was the focus of his wrath in his letter of 28 March too. Bose wrote to Nehru, “Was there nothing wrong in Sardar Patel making full use of the name and authority of Mahatma Gandhi for electioneering purposes?” The Bose brothers targeted Patel, but realised equally that Patel was a stalking horse and proxy for Gandhiji himself.

The tricky relationship between the closed group controlled by Gandhiji in the Congress Working Committee those days was patently unhappy with the entry of a powerful and popular outsider in Netaji.

Though Nehru privately and often publicly remained for most part on Netaji’s right side in this tussle. This proxy war resulted in Netaji leaving the Congress and taking up the path of freeing his country from the yoke of British rule by raising an army through a war time collaboration with the help of Axis powers inimical to the British Empire.

Leave a Reply