What most people don’t know is that Singh was a journalist, an identity that was intrinsic to his individuality, critical thinking abilities, and integrity of character…reports Saloni Poddar

“They may kill me, but they cannot kill my ideas. They can crush my body, but they will not be able to crush my spirit“.

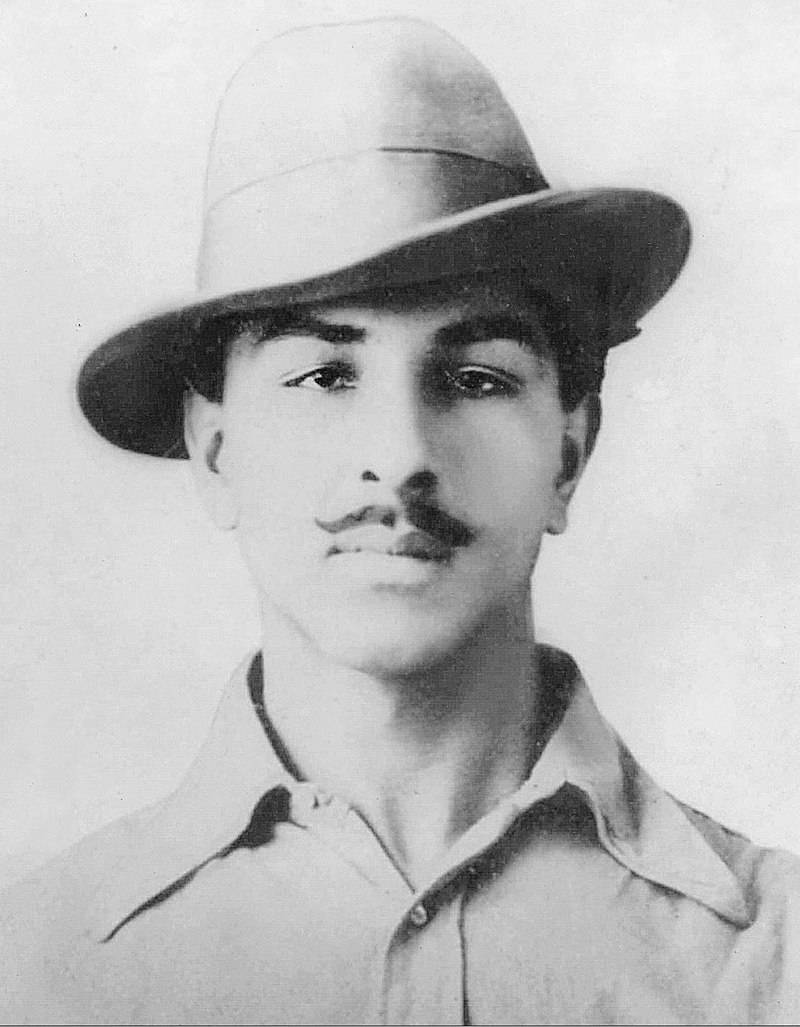

As patriotic Indians, we all know whose quote this is. If we even as much think about the freedom struggle of India, the first name that crops up in our mind is that of the revolutionary freedom fighter, Bhagat Singh. He is a household name, synonymous with patriotism.

There isn’t a shred of doubt about Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom but do we know enough about our hero? Was there more to him than being consumed with patriotism? Let us delve into the annals of history to find out more about him, his passions, and his life. But before that let’s just reiterate what is already known about this feisty, revolutionary young man.

Shaheed Bhagat Singh was born on September 27, 1907, in Lyallpur district of Punjab Province (now in Pakistan). At the age of 16-17 years, his family wanted him to get married but he wrote a letter to his father apologizing and telling him that service of the country was his prime goal in life and hence, worldly pleasures did not attract him. What most people don’t know is that Singh was a journalist, an identity that was intrinsic to his individuality, critical thinking abilities, and integrity of character. These journalistic endeavors made him stand out among his revolutionary contemporaries. He was a multi-lingual journalist who often wrote politically charged and socially-rooted stories based on pressing current issues, in Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, and sometimes even in English.

Bhagat Singh joined freedom fighter, Ganesh Shankar Vidhyarthi, in Kanpur and started writing for ‘Pratap’ under the pen name of Balwant Singh. His writing skills were honed under the banner of ‘Pratap’ where he translated the autobiographies of the great revolutionary. Shachidranath Sanyal’s ‘Bandi ki Jeevani’ (Life of Prisoner) in Punjabi, and that of Irish revolutionary Dan Breens ‘My Fight for Irish Freedom’ in Hindi. These translations gave an ideological approach to the ongoing freedom movements all over the country. His mentor, Vidhyarathi, was so taken by his work and personality that the former introduced Singh to the greatest revolutionary of those times, Chandrashekhar Azad, which was like a dream come true for Singh.

In his short but meaningful journalistic career, which ran parallel to his political life, he was associated with prestigious newspapers and magazines like Kirti, Pratap, Vir Arjun, Matwala, Prabha, and Bande Mataram, to name a few. Like his personality and ideals, Bhagat Singh’s writing was also explosive. He wrote such an article for ‘Pratap’ on 15th March 1926 titled, “Holi ke Din Rakt ke Chhinte” (Blood spatter on Holi)-

“Civil disobedience is at its peak. Punjab is ahead of everyone. Sikhs are rising in Punjab. There is a lot of passion. The Akali movement has started. Sacrifices are flowing”.

Singh wrote prolifically for the next few years and made a great impact on people’s minds with his works. In February 1928, he wrote an article about Kuka rebels under the alias of B. S. Sandhu. From March to October 1928, he compiled an anthology named ‘Aazadi ki Bhent Shahadatein’ (Martyrs at the Alter of Freedom). One particular article in this series was about Madan Lal Dhingra, an extraordinary revolutionary who sacrificed his life for freedom. Bhagat Singh wrote,

“Madan Lal was standing next to the noose and he was asked for his last words. He said – Vande Mataram. Salute to Bharat Mata! His body was buried in the jail itself. We Indians don’t even get to cremate him. Blessed be that Brave. Blessed is his memory. Many, many salutes to the precious hero of this dead country“.

This was a golden period in journalism as his words had the desired effect and woke people up from their slumber and made them realize that the need of the hour was upheaval and revolution. His writings became bolder and brasher with the passing years a historical edition of ‘Chand’ magazine was even banned by the British as it had many instigating articles by Singh. Hence, it was considered the ‘Gita of Indian Journalism’. It is rather unfortunate that a substantial body of his journalistic work has been lost to the ravages of unrecorded history as he often wrote under pseudonyms like ‘Virodhi’, ‘B. S. Sandhu’ and ‘Balwant Singh’. This was obviously done to remain anonymous as he was always under British scrutiny due to his active political life. Nevertheless, he couldn’t remain obscure for too long. On 8th April 1929, he wrote a pamphlet that shook the British government.

On the pamphlet was written –

“If the deaf is to hear, the sound has to be very loud“.

ALSO READ-House where Bhagat Singh hid in shambles