Anybody, be he a Muslim or the follower of any other faith, who stands between his pursuit of ‘freedom’ and him, is an ‘infidel’ whose elimination is part of the struggle started by him…reports Asian Lite News.

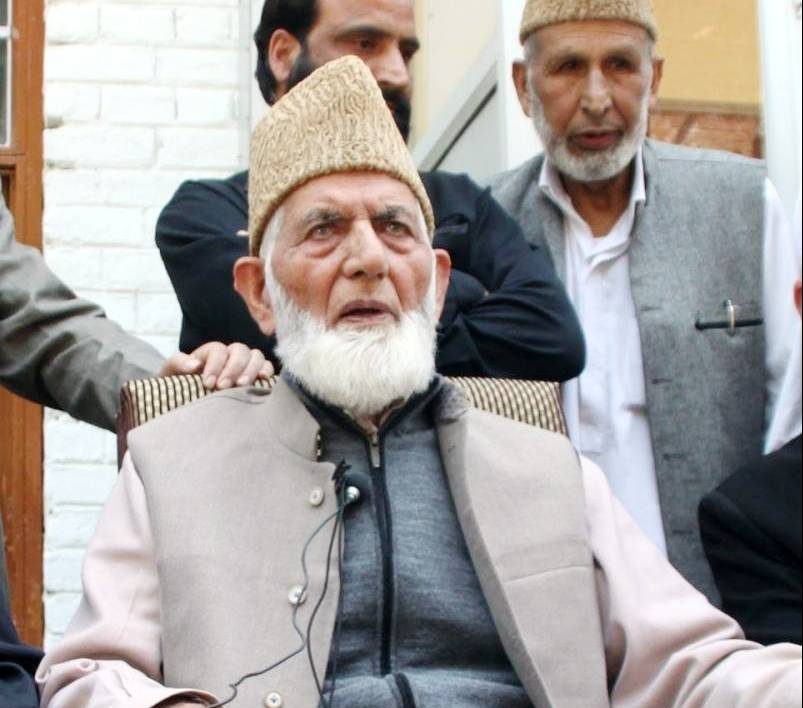

The succession of senior separatist leader, Syed Ali Geelani by Masrat Alam as the chairman of All Party Hurriyat Conference has much more to it than meets the eye.

Known as the ‘King of stone peters’ in Kashmir, Masrat Alam apparently heads his own faction of separatist leaders called the Muslim League.

Beyond the name of his so-called political outfit, there is nothing political about Masrat Alam.

He is a known hardcore separatist ideologue who stands for the merger of Kashmir with Pakistan.

That is Alam’s political belief, but he believes, beyond any shade of doubt, that his ‘political objective’ can only be achieved through an armed struggle.

No other separatist leader has been booked under the harsh Public Safety Act (PSA) in J&K as many times as Alam.

He holds the unenviable record of having been slapped with the PSA by the authorities over 40 times.

He was arrested in 2015 and is presently under detention.

He played a pivotal role to convert the Amarnath Shrine land row of 2008 into a bloody agitation.

Arson, intimidation, physical violence and murder of those who do not agree with his belief are some of the choice tools Alam believes must be used to fight the ‘infidels’.

Anybody, be he a Muslim or the follower of any other faith, who stands between his pursuit of ‘freedom’ and him, is an ‘infidel’ whose elimination is part of the struggle started by him.

The fact that Alam was nominated from across the border as the chairman of the Hurriyat Conference and as Geelani’s successor, has another interesting angle to it.

The inability of any of the over a dozen senior separatist leaders, including Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, Shabir Shah, Nayeem Khan or even Geelani’s son-in-law, Altaf Shah, proves the mistrust these separatist leaders have earned over the years in the eyes of their handlers in Pakistan.

Supporters of these separatist leaders try to rub off the salt from their wounds by saying these leaders are against violence.

This argument does not cut much ice because each time they called for a protest shutdown in Kashmir in the past, stone pelting and support from the armed outfits always came handy to make such ‘appeals’ successful.

Geelani, in his own lifetime, had been expressing public mistrust of all other leaders, including some from his own parent organisation, the Jamaat-e-Islami.

He broke loose from the United Hurriyat Conference in 2003 after accusing some of its constituents for fielding dummy candidates in the 2002 Assembly elections.

He also broke away from the Jamaat in 2008 forming his own party called the ‘Tehreek-e-Hurriyat’.

Those close to him argue that he had been betrayed by almost all senior separatist leaders.

The truth about whether Geelani disliked his separatist colleagues for not accepting him as their undisputed leader or for reasons of their divided loyalties will now remain interred with him.

The net result has been that the political face of separatism in Kashmir was finally lost in Geelani’s death.

Masrat Alam as the chairman of the Hurriyat Conference will always remain as somebody for whom dialogue and engagement are as meaningless today as they were yesterday.