All Russian literature is not grim, pessimistic, plodding tracts and can hold its own, using a range of genres and styles to reflect the human condition and its times…writes Vikas Datta

Literary traditions take centuries to develop, let alone acquire a following outside their own linguistic realm. Russian literature, however, saw an accelerated rate to global popularity within 200 years.

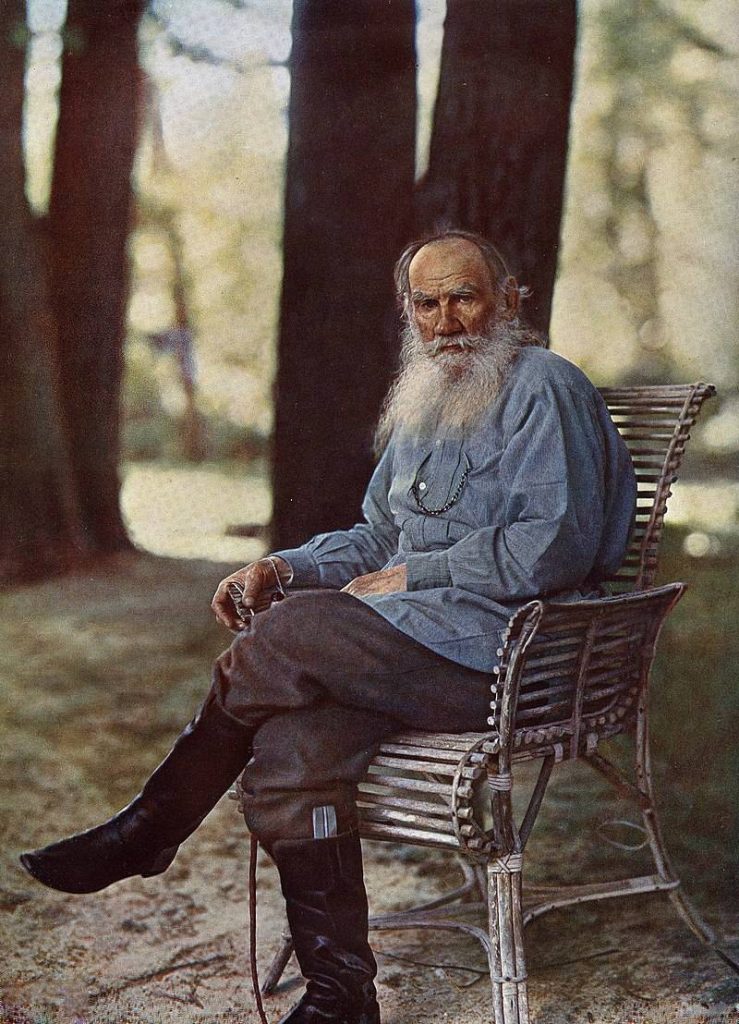

After nearly a millennium of an oeuvre comprising mainly folk/fairy tales, or the odd historical chronicle, it started to make its presence felt from the early 19th century with Pushkin and Gogol, and then, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Bulgakov, Pasternak, Nabokov, Akhmatova, and their ilk have ensured its continuing prominence across genres.

But, Russian literature, especially of the “Classical School”, which comprises its best-known works, has also laboured under a rather unjust and fearsome perception.

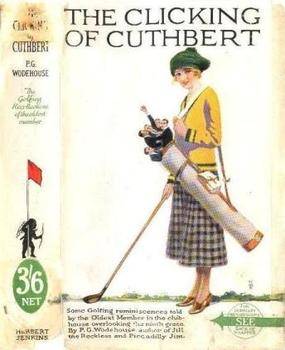

Take views like: “This Vladimir Brusiloff to whom I have referred was the famous Russian novelist. … Vladimir specialised in grey studies of hopeless misery, where nothing happened till page three hundred and eighty, when the moujik decided to commit suicide.” (“The Clicking of Cuthbert” by P.G. Wodehouse)

Or: “Freddie experienced the sort of abysmal soul-sadness which afflicts one of Tolstoy’s Russian peasants when, after putting in a heavy day’s work strangling his father, beating his wife, and dropping the baby into the city’s reservoir, he turns to the cupboards, only to find the vodka bottle empty.” (P.G. Wodehouse again)

Then, vet James Herriot, in his memoirs, reveals how a colleague used to read the opening para of “The Brothers Karamazov” to lull himself to sleep.

Author Viv Groskop, whom we will return to later, observes some common views about Russian literature are that it is “deep”, “difficult”, or require a wider level of reference than the casual reader can aspire to. “You’ll never understand X if you haven’t read Y,” she says.

And then there is the issue of names. Groskop quotes a Danish academic, otherwise impressed by Russian literature, bemoaning: “Why do they (the characters) all have to have forty-seven names?”

While works such as the hefty “War and Peace”, and many other 19th-century novels, are probably responsible for the length part, and the “confusing” names are due to the Russian naming tradition comprising the patronymic, and the widespread use of diminutives, affectionate and otherwise, which needs getting used to, the issue of the content is not quite justified.

All Russian literature is not grim, pessimistic, plodding tracts and can hold its own, using a range of genres and styles to reflect the human condition and its times. Let’s look at half-a-dozen lesser-known works spanning the Golden Age to the present day, and subsequently available in English, which unfortunately leaves out writers such as Yulian Semyonov, creator of the Soviet ‘James Bond’ (unfortunately only one of the series is in English) and fantasy/science-fiction virtuoso Andrei Belyanin.

“Oblomov” (1859), Ivan Goncharov’s second novel, is especially known for how it takes its young titular nobleman protagonist 50 pages — around a tenth of the book’s length — to get out of his bed, in which he spends most of his life, onto a sofa.

Sinking into debt by refusing to take any interest in running his estate deep in the countryside, our slothful character spends the entire account trying to avoid any responsibility, including in love, despite the efforts of well-meaning and more focused friends, before passing on to his desired state of perpetual rest.

Known for taking the “superfluous man”, Russia’s unique contribution to literary archetypes, to a new high — or rather a low, if you contrast it with Pushkin or Lermontov’s creations — it is a trenchant satire on the state of Tsarist Russia’s aristocracy and shows why the revolution became inevitable.

“The Death of the Vazir-Mukhtar” (1928) — either the Susan Causey (2018) or the Anna Kurkina Rush/Christopher Rush translation — by Soviet literary historian and critic Yury Tynyanov, chronicles the last year of the early 19th-century Russian playwright, Orientalist, polyglot, and diplomat Aleksandr Sergeyevich Griboyedov after he returns to Moscow and St Petersburg following a successful diplomatic mission in Persia, and then returns to Tehran on a new mission when he dies in an attack on the embassy by an enraged mob protesting a new treaty.

Featuring a certain quirkiness in its style, i.e. the use of a heavy Russian bureaucratic language, with a spate of lyrical, psychological, and historical digressions, Tynyanov’s modernist theories of literature, comprehensive and sometimes striking psychological insights into many characters, even small-time, across a range of cultures — Russia, Caucasian, and Qajar-era Persia, it is a thoroughly well-researched piece of historical fiction.

“The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin” (1969), by dissident writer Vladimir Voinovich, is the picaresque tale of the absurdities that even totalitarianism cannot avoid.

It tells of a bumbling, unlikely soldier who is posted to a backwater on the eve of World War II, forgotten by his superiors and labelled a deserter, and how he holds off a squad of the German secret service — winning a medal, before getting arrested.

“Pretender to the Throne: The Further Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin” (1979) and “A Displaced Person: The Later Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin” (2007) see him brave out his interrogation, and then made to emigrate to the US, from where he returns as head of an official delegation during the Perestroika era.

Science fiction was always a favoured area for Soviet writers unwilling to toe the official line since it allowed them to use alien worlds to portray social and political situations disallowed in more realistic settings.

Amid a glittering lineup are brothers Arkady Natanovich Strugatsky and Boris Natanovich Strugatsky, whose over two dozen works, written in collaboration, have been quite influential in the genre.

Two which stand out are “Monday Begins on Saturday” (1964), about the personnel and activities at a Soviet research institute dedicated to studying magic and the supernatural, teamed up with the inept administrators who run it. “Tale of the Troika” (1968) continues the satire of the Soviet scientific set-up and its political superstructure.

Then, “One Billion Years to the End of the World” (1977; originally published in English as “Definitely Maybe”), which begins rather on a comic note and gradually gets more ominous as a bunch of researchers, both scientific and of social science, wonder why they are not let being allowed to work on, and their responses.

Among the post-Soviet period, there is Grigori Chkhartishvili alias Boris Akunin’s Erast Fandorin crime thriller series, set in the dying decades of Tsarist Russia, but that deserves an instalment of its own.

Vladimir Nabokov

Tiynyanov

And if you look for some way to acquaint yourself with the classics only, without reading them in their entirety, then Groskop’s “The Anna Karenina Fix: Life Lessons from Russian Literature” gives you an insightful look into 11 of them from “Dead Souls” to “Dr Zhivago”. It may inspire you to read them too.

ALSO READ-‘LinenVogue La Classe’ to inspire a sense of reminiscence