Given the cost of wood and the absence of wood storage facilities most of the state’s crematoriums face the same dilemma. Villagers of Uttarakhand have been left with no options…reports Inder Bisht

In January this year, 50-year-old Govind Gopal, an environmental activist from Danya — a small tourist stopover between Almora and Pithoragarh in Uttarakhand — went on a hunger strike to raise concerns about and demand accountability for the rampant felling of trees for cremations.

He called for a green cremation facility at the local crematorium and the establishment of wood storage facilities in crematoriums where it’s not available.

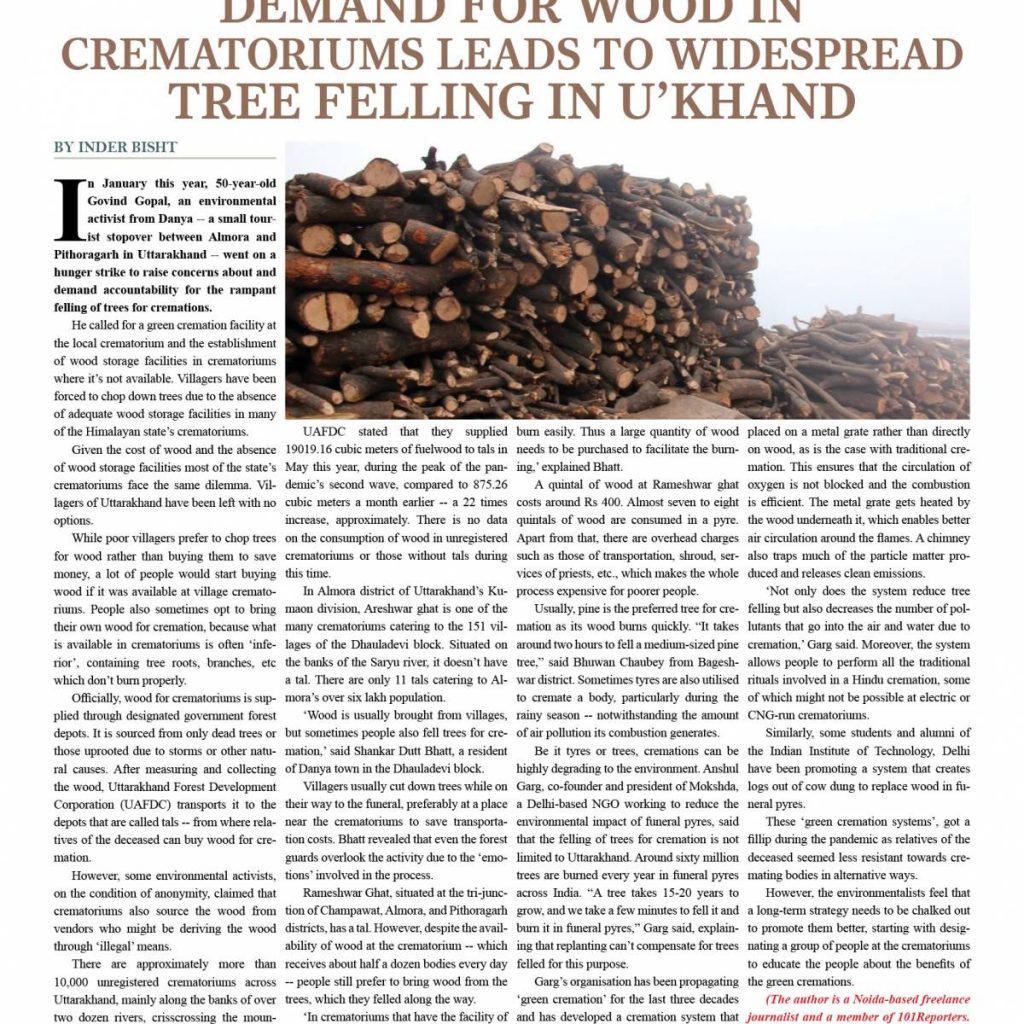

Villagers have been forced to chop down trees due to the absence of adequate wood storage facilities in many of the Himalayan state’s crematoriums.

Given the cost of wood and the absence of wood storage facilities most of the state’s crematoriums face the same dilemma. Villagers of Uttarakhand have been left with no options.

While poor villagers prefer to chop trees for wood rather than buying them to save money, a lot of people would start buying wood if it was available at village crematoriums. People also sometimes opt to bring their own wood for cremation, because what is available in crematoriums is often ‘inferior’, containing tree roots, branches, etc which don’t burn properly.

Officially, wood for crematoriums is supplied through designated government forest depots. It is sourced from only dead trees or those uprooted due to storms or other natural causes. After measuring and collecting the wood, Uttarakhand Forest Development Corporation (UAFDC) transports it to the depots that are called tals — from where relatives of the deceased can buy wood for cremation.

However, some environmental activists, on the condition of anonymity, claimed that crematoriums also source the wood from vendors who might be deriving the wood through ‘illegal’ means.

There are approximately more than 10,000 unregistered crematoriums across Uttarakhand, mainly along the banks of over two dozen rivers, crisscrossing the mountainous state. However, only a hundred-odd crematoriums have a tal at the facility.

UAFDC stated that they supplied 19019.16 cubic meters of fuelwood to tals in May this year, during the peak of the pandemic’s second wave, compared to 875.26 cubic meters a month earlier — a 22 times increase, approximately. There is no data on the consumption of wood in unregistered crematoriums or those without tals during this time.

In Almora district of Uttarakhand’s Kumaon division, Areshwar ghat is one of the many crematoriums catering to the 151 villages of the Dhauladevi block. Situated on the banks of the Saryu river, it doesn’t have a tal. There are only 11 tals catering to Almora’s over six lakh population.

‘Wood is usually brought from villages, but sometimes people also fell trees for cremation,’ said Shankar Dutt Bhatt, a resident of Danya town in the Dhauladevi block.

Villagers usually cut down trees while on their way to the funeral, preferably at a place near the crematoriums to save transportation costs. Bhatt revealed that even the forest guards overlook the activity due to the ’emotions’ involved in the process.

Rameshwar Ghat, situated at the tri-junction of Champawat, Almora, and Pithoragarh districts, has a tal. However, despite the availability of wood at the crematorium — which receives about half a dozen bodies every day — people still prefer to bring wood from the trees, which they felled along the way.

‘In crematoriums that have the facility of wood storage, an assortment of wood is provided that includes roots of trees that don’t burn easily. Thus a large quantity of wood needs to be purchased to facilitate the burning,’ explained Bhatt.

A quintal of wood at Rameshwar ghat costs around Rs 400. Almost seven to eight quintals of wood are consumed in a pyre. Apart from that, there are overhead charges such as those of transportation, shroud, services of priests, etc., which makes the whole process expensive for poorer people.

Usually, pine is the preferred tree for cremation as its wood burns quickly. “It takes around two hours to fell a medium-sized pine tree,” said Bhuwan Chaubey from Bageshwar district. Sometimes tyres are also utilised to cremate a body, particularly during the rainy season — notwithstanding the amount of air pollution its combustion generates.

Be it tyres or trees, cremations can be highly degrading to the environment. Anshul Garg, co-founder and president of Mokshda, a Delhi-based NGO working to reduce the environmental impact of funeral pyres, said that the felling of trees for cremation is not limited to Uttarakhand. Around sixty million trees are burned every year in funeral pyres across India. “A tree takes 15-20 years to grow, and we take a few minutes to fell it and burn it in funeral pyres,” Garg said, explaining that replanting can’t compensate for trees felled for this purpose.

Garg’s organisation has been propagating ‘green cremation’ for the last three decades and has developed a cremation system that uses one-third of the wood that a typical cremation requires. In this system, the body is placed on a metal grate rather than directly on wood, as is the case with traditional cremation. This ensures that the circulation of oxygen is not blocked and the combustion is efficient. The metal grate gets heated by the wood underneath it, which enables better air circulation around the flames. A chimney also traps much of the particle matter produced and releases clean emissions.

‘Not only does the system reduce tree felling but also decreases the number of pollutants that go into the air and water due to cremation,’ Garg said. Moreover, the system allows people to perform all the traditional rituals involved in a Hindu cremation, some of which might not be possible at electric or CNG-run crematoriums.

Similarly, some students and alumni of the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi have been promoting a system that creates logs out of cow dung to replace wood in funeral pyres.

These ‘green cremation systems’, got a fillip during the pandemic as relatives of the deceased seemed less resistant towards cremating bodies in alternative ways.

However, the environmentalists feel that a long-term strategy needs to be chalked out to promote them better, starting with designating a group of people at the crematoriums to educate the people about the benefits of the green cremations.

(The author is a Noida-based freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)

ALSO READ-Muslim woman turns cremator at a Hindu crematorium

Leave a Reply