The AMC estimated that the project would have cost Rs 13 crore if it had been done through contracts given to private stakeholders but instead cost the city only 1 crore, thanks to the involvement of the residents…reports Abhilasha Agrawal

Residents of Aurangabad in Maharashtra got enthusiastically involved over many Saturdays early this year to clean up the Kham river as part of the drive to restore its ecological health, sustainability and aesthetic value. The restoration campaign — ‘Our River, Kham River’ — started in January under the supervision of Astik Kumar Pandey, Municipal Commissioner of Aurangabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), and featured a range of beautification activities.

Santosh Ambe, a local who lives near the river, praised the project, “I am truly thankful to the municipal commissioner for taking steps towards restoring the river. No kind of encroachments have been done in this campaign, neither were nearby residents asked to relocate. Hence, we are happily supporting the initiative and creating awareness for the future too.”

Originating in the Jatwada Hills on the outskirts of Aurangabad, the Kham flows through the city before merging with the Godavari at Yeshgavhan. It has been part of residents’ lives since the Mughal era. First known as Khadki, Aurangabad was made a capital city by Malik Amber, the prime minister of Murtaza Nizam Shah II, Sultan of Ahmadnagar. He used the river’s valley and various nullahs to meet the city’s water requirements and constructed freshwater aquaducts called Nahar-e-Ambari — a type of hydraulic water carriage system — which ensured the Kham’s perennial flow.

Citizens on the job every Saturday

Over the years the river has degraded through a toxic brew of domestic waste, animal carcasses, industrial pollution, population growth, rampant encroachment, and increasing urbanisation. Water shortages galvanised Commissioner Pandey to engage residents, social groups and NGOs in reviving the river by educating them about its historic significance to their city. Between 200 and 250 showed up every Saturday from 8 am to 11 am to pick up dry waste (150 tonnes, according to the AMC’s sanitation department) and plant trees, while earthmovers, JCBs and tippers did the heavy lifting. The public lent gaiety to the proceedings by singing songs about religious devotion and environmental awareness. Some even shook a leg.

The AMC estimated that the project would have cost Rs 13 crore if it had been done through contracts given to private stakeholders but instead cost the city only 1 crore, thanks to the involvement of the residents.

Nandkishor Bhombe, head of solid waste management at AMC, noted the project’s environmental importance, “I am happy the people of Aurangabad have shown such dedication towards the river and I insist they continue to show the same concern in the time to come. The demands of future generations will get fulfilled only if we take good care of our natural resources.”

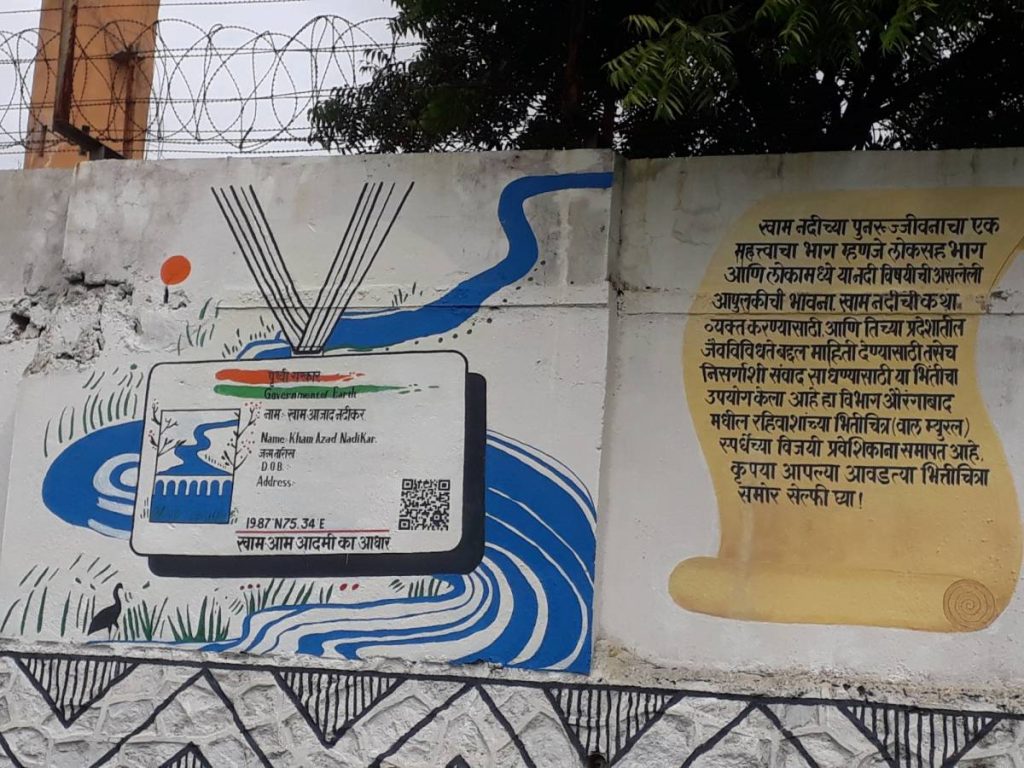

Ramesh Gaikwad, a sanitation worker, was amazed with all the support and engagement from the public. “The city has always been divided by religious differences. But over the last decade, people have started to show a sense of love towards their city. This has been possible due to education, awareness and empowerment of women. I have seen all these factors contributing to the rejuvenation of Kham river recently. Creating an amphitheatre out of tyres and painting the story of Kham are some unique ideas by the women and youth which were given the green flag by the corporation.”

Planting Miyawaki forests

The project also involved planting diverse saplings along the river’s banks using the Miyawaki method (two to four saplings per square metre) to bolster biodiversity. As many as 10,000 bamboo trees — known for increasing afforestation and playing a role in combating climate change — have been planted along the Kham. “This type of plantation has helped us plant all varieties at closer distances. As the Miyawaki forest sustains itself, it will need fewer efforts in the future,” Bhombe said.

Aditya Tiwari, an ecologist working in Aurangabad, underscored the Miyawaki method’s relevance. “The Japanese method of tree plantation has become the centre of attention in the Cantonment Board area. We are focusing on the ecological transformation of the river via urban plantation.” Seedlings are planted at very high densities in a packed space. “Mostly straight varieties of trees can be grown in a smaller area. We have focused on planting bamboo, nilgiri or eucalyptus and banana trees instead of neem and banyan that utilise a large area,” Tiwari added.

During the clean-up, the team came across a rich ecosystem of snakes, freshwater turtles, crabs, fish, butterflies as well as 85 species of indigenous plants, including medicinal herbs used by Mughal hakims.

Looking ahead into the past

In addition to encountering plenty of animal species and indigenous flora, the clean-up team stumbled upon those hidden underground nahars built by Malik Amber.

There were 12 nahars in Aurangabad and they supply drinkable water to different parts of the city, according to the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) and, amazingly, they still carry freshwater. For centuries, citizens of the city had been using the ‘manholes’ or strong and high rectangular tanks to access and clean the nahars.

To preserve and use this precious resource, nearly 16 farm ponds (shetal in Marathi) have been created and submersible water pumps have been installed to lift the underground water. All broken water pipelines along the nahar (which were laid to help the water along in places where gravity couldn’t do the trick) have been replaced with new clay ones.

Five months after the clean-up drive, a water index survey by Ecosattva showed that the river’s biochemical oxygen demand has come down to 40-45 per litre from a high of 50, which means that the Kham is now ready for irrigation. Smriti Salve, who lives along the river, said the proper deepening and widening of the river has prevented flooding in their homes despite the heavy rainfall this year.

So, the river’s future now looks promising. Hanif Ansari, who participated in the project, expressed how he felt about it. “Being a sanitation worker, I have been associated with river cleaning for a decade. But never before have I felt so connected with the environment. I have given my time and effort to this work, so it is my duty to take good care of the natural resource now. I even brought my children to learn on the site. They are the future.”

ALSO READ-Why India needs a third aircraft carrier?

Leave a Reply