Pakistan’s education crisis is marked by a shockingly large number of out-of-school children, very low learning outcomes, wide achievement gaps and inadequate teacher efforts, writes Dr. Sakariya Kareem

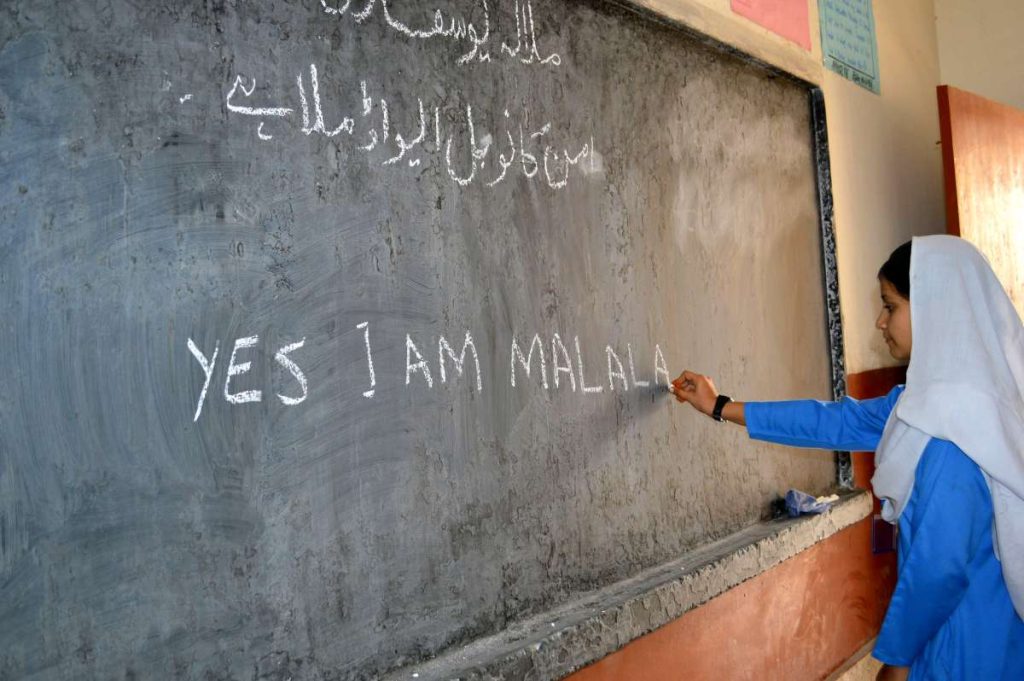

Recently Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai expressed concern over Pakistan’s education crisis. In a letter to Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, she wrote “Currently, 26 million children — predominantly girls in the poorest districts of Pakistan — remain out of school. Furthermore, more than 200,000 teachers’ seats are vacant nationwide.” “This gap is severely affecting the functioning of schools and negatively impacting student retention and quality of schooling. Our collective aim should be to design a measurable, realistic plan to bring these numbers down significantly over the course of your term,” she added.

Although through her letter Malala has highlighted the crisis in Pakistan’s education sector, the actual number of out-of-school children in the country stands at a startling 28 million, somewhat more than what she has quoted. Despite tall claims made by successive governments to enroll out-of-school children, the number of such kids continues to grow at a rapid pace.

Pakistan’s education crisis is marked by a shockingly large number of out-of-school children, very low learning outcomes, wide achievement gaps and inadequate teacher efforts.

In January this year, a report on the performance of the education sector was released by the Pakistan Institute of Education, a subsidiary of the education ministry revealed a lack of funds, poor pupil-teacher ratio, missing basic facilities as well as 26 million Out of School children (OOSC) in Pakistan. The report highlighted that an alarming 26.21 million – basically, 39 percent of children in Pakistan are out of school. OOSC are defined as children of school going age that are not going to school. The compulsory range of school going age is stipulated as five to 16 years under article 25-A of the Constitution. The number of OOSC stands at 11.73 million in Punjab, 7.63m in Sindh, 3.63m in KP, 3.13m in Balochistan, and 0.08 million in Islamabad. The percentage of out-of-school children decreased from 44 percent in 2016-17 to 39 percent in 2021-22.

More than 50 per cent of all school going age children are out of school in 17 out of 28 districts in Balochistan. District Shaheed Sikandarabad has the highest proportion of OOSC in Balochistan at 76 per cent, with Sherani following at 70 percent of out of school children between the ages of five and 16 years.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, district Kohistan has the highest proportion of OOSC at 60 per cent.

The results from key assessments conducted by the National Assessment Wing, specifically the Trends in International Mathematics & Science Study (TIMSS) and the National Achievement Test (NAT), highlighted the urgent need to improve learning outcomes among students. The report said that in 2021-22, spending on education remained 1.7percent of GDP.

In terms of enrolments, these happen later than required, with a lack of emphasis on early childhood education leading up to class 1. Drop outs start to happen between 9-11 years of age. The dropout ratio rises steadily with age. However, the proportion of children who have never attended school remains overwhelming at all age levels.

Large schools across Pakistan simply lack toilets, potable water among other basic facilities. As per the report, only 23 percent of primary schools in Balochistan have access to potable water. Only 15 percent schools in Balochistan have electricity. In terms of toilet facilities scarce in all primary schools, across Pakistan, Balochistan fares worst with 77 percent primary schools, 31 percent middle schools, and four percent high schools not having toilets for students. In Sindh, 43 percent primary schools do not have toilet facilities. In Balochistan, the situation is alarming. In Azad Kashmir, 58 percent primary, 34 percent middle, and 23 percent high schools do not have this facility.

OOSC in Pakistan can be compared to that in the Sub-Saharan countries. It is one of the major challenges faced by the education sector of the country. Poverty and lack of awareness were major factors behind this issue. According to a teacher from Islamabad, “In most of the cases, the kids do labour work to help their families and the children will not be able to join schools till this issue is resolved.” Governments have highlighted very slow progress on education participation, completion and closing of the gender gap”, and successive cabinets have approved plans for bringing OOSC to schools, but practically no serious steps have been taken to handle this crisis.

Furthermore in terms of the quality of education. Consider this statistic. The result of the last CSS examination, announced on September 18, 2023 reflects the quality of graduates being produced by our higher educational institutions (HEIs). The Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC) conducts a competitive examination, commonly known as CSS, for recruitment of officers at the starting stage in the civil services of Pakistan. As per the FPSC, at least 20,000 candidates attempted the written part of the examination, of whom only 393 candidates, or 1.94 percent, passed.This reflects the falling standards of Pakistan’s education over several years. One of the FPSC reports states that many of the candidates were not even familiar with elementary mathematics. Many candidates “did not even know the direction of a simple compass, confusing north with south and east with west.” Almost all its reports complain about the absence of analytical skills among the candidates who mostly reproduce “crammed knowledge.”

An inclusive education does not discriminate by gender, language, religion, etc. On gender, discrimination is manifest at the outset when income constrained families spend more to educate sons than daughters. Children whose home language is not English or Urdu cannot acquire elementary education in their own language even if their parents want. The exclusion of languages such as Sindhi and Balochi means not only their slow death but also the withering of their associated cultures and identities.The religious content of one religion is diffused throughout textbooks prescribed for secular subjects. This practice is justified by the argument that Pakistan is overwhelmingly Muslim (97.5 per cent), which makes it alright to propagate predominantly Islamic content.

Thus, Pakistan’s school education is neither inclusive nor equitable and is departing further from these objectives. Because Pakistan’s ruling elite is just playing along with the UN? One of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) obligates the country to provide inclusive and equitable education for all. The SDGs were preceded by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for 15 years. None were attained in Pakistan without any analysis of the reasons for the failure. Instead, the country signed on to a new set of goals with a fresh lease of 15 years during which officials would continue to hold meetings and participate in conferences. Meanwhile, the people in whose name the exercise is being conducted are largely excluded from the conversation.

Leave a Reply