Although the conventional wisdom is that Xi would direct his firepower across the Taiwan straits, the probability is higher that he may instead seek to challenge India by 2023 on some of the battlefields of the Himalayan massif, writes Prof. Madhav Nalapat

The race in Asia to modernize was first launched by Japan in 1868, with the restoration of the Imperial system under Emperor Meiji, casting aside the oppressive rule of the Shogunate. Certainly from the time of Emperor Meiji onwards, the Imperial system gave substantial latitude to large segments of Japanese society. Such a downward dissemination of Imperial authority generated forces within Japan that placed the country on the track towards modernisation.

In India, after getting free of the debilitating rule of the British Empire in 1947, Mahatma Gandhi sought to return India to the past, the pastoral paradise that he believed once existed and was the best way to the future. His chosen Prime Minister of the Republic of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, turned to the Soviet Union for inspiration, straitjacketing the private sector and giving the state-owned sector the “commanding heights” of the economy, a process carried forward by his daughter and eventual successor as PM, Indira Gandhi. From the start, the post-1947 Government of India neglected to spread the dissemination of knowledge of the English language to the wider population.

This was under the belief that the language was an instrument of colonial oppression rather than a means towards modernisation, although this view did not prevent the political class as well as the higher rungs of the administrative system from relying on the international link language, especially while educating their children. At the same time as this was being done by them, the usage of English in the state-funded schools that were the sole alternative of the poorer sections of society was choked into insignificance, a policy of ignoring available tools of national betterment that persists to this day. Indeed, from the 1980s onwards, the Chinese Communist Party leadership has regarded the still largely colonial construct of the Indian administrative system as being the best guarantor of the continuing superiority of the PRC over India in the economic and technological spheres.

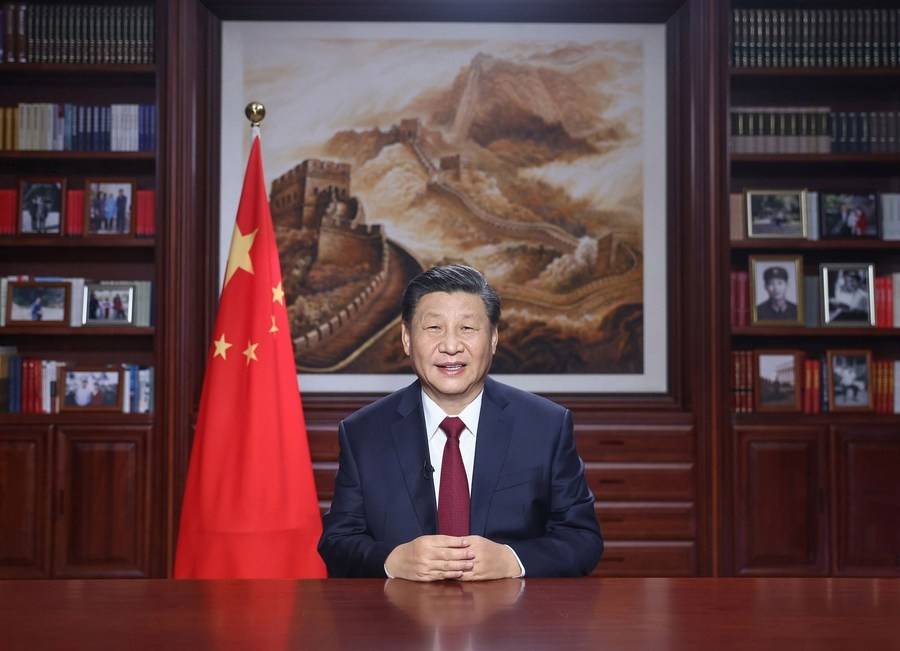

The good news for India (and its Quad partners) is that General Secretary Xi Jinping, since his takeover in 2012 of the governance mechanism of the PRC, has adopted the Soviet model of state supervision and control over an increasing number of activity segments. The CCP under Xi is not content with merely having the commanding heights of overall authority, but wants to micro-manage almost every segment of society and the economy, with consequences for the future their country that are unclear at the moment.

XI CENTRALISES AUTHORITY

Whether it be the UK, the US, Japan or China during the Deng-Jiang-Hu period, much of economic and societal progress hinged on the devolution of authority best expressed in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for “minimum government, maximum governance”. Efforts by authorities at the central, state and local levels to control wide activity bands end in sub-optimal results of the kind witnessed by the persistence for decades of an “Indian Rate of Growth” of around 2% per year. This puny performance was witnessed through several squandered decades of an excess of government at the expense of governance. Those who seek to control everything end up controlling nothing, a lesson that appears to have been beyond the comprehension of many individuals in the governance system in India.

ALSO READ: India-Taiwan ties are quietly cementing amid friction with China

What is to be seen is whether the PRC under Xi Jinping will fare any better, now that the CCP General Secretary has gone to the centralising mode that was current through much of the 1917-1992 history of the USSR. When this centralising tendency was briefly abandoned by Lenin during 1922 in his New Economic Policy, the results were good. The NEP was abandoned by General Secretary J. Stalin in 1928, intent as he was on centralising authority in the Office of the General Secretary (OGS), much as Xi Jinping is attempting at present. Stalin abandoned his stifling controls only during wartime, when the disasters suffered by Soviet forces at the hands of the Wehrmacht forced him to reconsider his earlier stance that all power had to reside in the OGS, much the way Adolf Hitler sought to centralise all power in the person of the German Fuehrer, i.e., himself.

The relaxation in centralisation of decision-making brought about an immediate improvement in the performance of the Soviet armies, which were able to quickly respond to the situation developing on the battlefield rather than awaiting orders from STAVKA, the High Command of the Soviet military, which in the early stages of the 1941-45 war with Germany used to toss each such decision to the level of the Office of the General Secretary. Small wonder that more than three million Soviet troops were killed or captured before Stalin’s disastrous policy of draining all initiative from field commanders was abandoned by him at the start of 1943.

Just as was the case under Mao Zedong, in the Xi CCP, loyalty means obedience to the will of the party supremo. To this has been added the actual reality of micro-management during the Xi era, unlike during the Mao period (1949-76), when those identified as Mao loyalists were given wide latitude to operate. Across the PRC bureaucracy, the ouster is instant of those who—even through stray comments made by them on current policies that have been picked up by modern surveillance systems bought from Israel and Europe besides being “borrowed”, usually from the US—question any of the decisions of the growing list of authorities under the direct supervision of the Office of the General Secretary (OGS) of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The assumption made by the CCP OGS in the expansion of control introduced since 2012 is that the General Secretary (directly or through his secretariat) is incapable of making mistakes or taking any decision that is not entirely to the benefit of the 1.4 billion citizens of China. Any individual who doubts such a proposition is ipso facto an “anti-Party element” needing to be removed from office. Although it is difficult to gauge the situation in China, as a general proposition, it is evident that such a system leads to the atrophy of initiative, the factor that has been primarily responsible for the manner in which the PRC has leapfrogged over its competitors (including Japan, Germany and India) to become the world’s other superpower, denying the US its post-1992 perch as the only superpower in the world.

Servility and its attendant flattery are seldom synonymous with executive ability or the talent to identify improvements and work on their implementation, and by 2023-06 it will be clear whether the PRC governance system and its economy has entered into the state of entropy that began in the USSR during the later phases of the Brezhnev era.

SMART POLICY NEEDED FOR TECH

Technology comprises thoughts welling up in the human mind, and not of steel and glass skyscrapers marring urban skylines. In his efforts at forcing the tech giants of China, for instance, to surrender their data and indulge in activities that would attract banishment from markets and jail terms for local managers in several countries, the General Secretary may discover that the information such turns of the screw generate may be of much less value than the lesser quantities secured by more commonplace methods of data sharing, such as the protocols followed by large global tech players within their home countries. A country concerned about its own security would never permit the egress of toolkits such as Pegasus into sensitive cyberspace, for the reason that most of the critical data accessed by such platforms goes only to the company owning the technology and not to the clients making use of the same.

After that, it would be up to the concerned company to decide which entities it would be willing to share such data with, often at a steep price, especially when such entities have interests. Given that such a fact is well known, it is difficult to believe the reports that the Government of India, which has international experts such as NSA Doval in charge of security, would purchase toolkits such as Pegasus to conduct surveillance on sensitive targets. The data from such snooping would go directly to a foreign company, NSO, and there would be no way for the GoI to know whether the data subsequently handed over to its agencies or their intermediaries was complete or only partial. Which is why the allegations made against the Modi government in the Pegasus matter are likely to have no foundation in fact.

MILITARY CORE OF XI POLICY

The parade ground uniformity and heel-clicking instant obedience sought by Xi seldom generate the dynamism needed for technologies to develop at the period of greater than usual flux that has been created by the Mao-style assertive style of functioning of the Xi system. After having taken over Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Aksai Chin, Tibet and Xinjiang, Mao did not covet any additional territory, withdrawing in 1962 itself even from Indian territory that had been claimed as forming part of the territory of the PRC. In contrast, the PLA under Xi seeks to gain additional territory both on land and sea, unable to understand that a less aggressive mode of activity would have created the atmosphere needed for genuine “Win-Win” solutions, such as what was attempted to be done during 2018 by PM Modi in Wuhan.

ALSO READ: Blinken expresses concerns over China’s growing nuke arsenal

In its place, what is being witnessed by the international community is an unceasing effort by General Secretary Xi and his suite of loyalists to fashion Zero Sum situations that invariably get sought to be tilted to favour the PRC side. It is too early to say whether the “All or Nothing” gamble of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping will succeed or fail in its efforts at upending the world order so as to create both a Eurasian landmass as well as an Indo-Pacific water mass that is dominated by Beijing. The only chance of such a manoeuvre succeeding is if the big democracies (such as India and the US) make a large enough number of policy errors such as would facilitate the attainment of the expansive objectives set by the CCP General Secretary during 2015-18 for the bureaucracy that he heads.

XI MAY NEED MILITARY SUCCESS

Should the CCP leadership’s estimates about the manner in which Xi Jinping Thought will create changes in the PRC economy prove wrong, there will be pressure on General Secretary Xi to use other pathways towards retaining the “Mandate of Heaven” (i.e., the acquiescence of the population) for continuing his rule. A military victory over major adversaries such as India and the US would assist in securing sufficient public support. Although the conventional wisdom is that Xi would direct his firepower across the Taiwan straits, the probability is higher that he may instead seek to challenge India by 2023 on some of the battlefields of the Himalayan massif. The odds for this would rise were Moscow to succeed in keeping Delhi sufficiently apart from Washington in a military sense, something that the numerous statements from Washington and Delhi about the Quad being just another version of a fusion of the Salvation Army with the International Red Cross seem to indicate. Should the Central Military Commission (CMC) miscalculate, and the Indian armed forces prevail in any such a conflict, the position of Xi within the CCP will become shaky.

General Secretary Xi has placed his and his country’s credibility on the tip of the PLA spear, and should that weapon fail in actual combat, the loss of prestige would be as disastrous domestically and internationally for Xi Jinping as the 1962 defeat of the Indian Army (the Air Force remained a spectator to the two-month war, for reasons yet to be made public) was for Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Had there not been such a defeat, it would not have been necessary for family loyalists to have placed Lal Bahadur Shastri in the South Block office of the Prime Minister rather than install Indira Gandhi immediately after the demise of Nehru, in the same manner that Rajiv Gandhi was sworn in as PM after the assassination of his mother on October 31, 1984. Another threat to the “Mandate of Heaven” would be an economic collapse, such as would be inevitable were the decoupling from China of numerous external investors to gather speed over the next few years.

LONGTIME PRECEDENT ABANDONED

Xi Jinping is following the playbook of the major European powers in the 18th and 19th centuries in an effort at building up a Pax Sinica. In this, he has departed from the precedents set by Mao after the annexation of Tibet, of not pressing territorial claims, by seeking expansion of territories that were annexed to form part of China. The world of the 21st century is not what it was during the 18th or 19th centuries, the history of which the CCP core has made its cadres learn almost by rote. Nor is Europe what it was, nor the countries once colonised by that continent. Despite the catechism that Xi Jinping Thought is infallible, abandoning a precedent that stretches back to 1956 may not prove to have been the best decision taken by CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping.