He writes in the book that before the Liberation (he was eight then), he was probably not even aware that there was a country called India…writes Vishnu Makhijani

Iconic Goan musician Remo Fernandes views colonisation as “a totally illegal and criminal act perpetrated exclusively by European countries”, and says the upside of the Liberation from Portuguese rule in 1961 “for a musically minded pre-teen was the introduction of English and American music”.

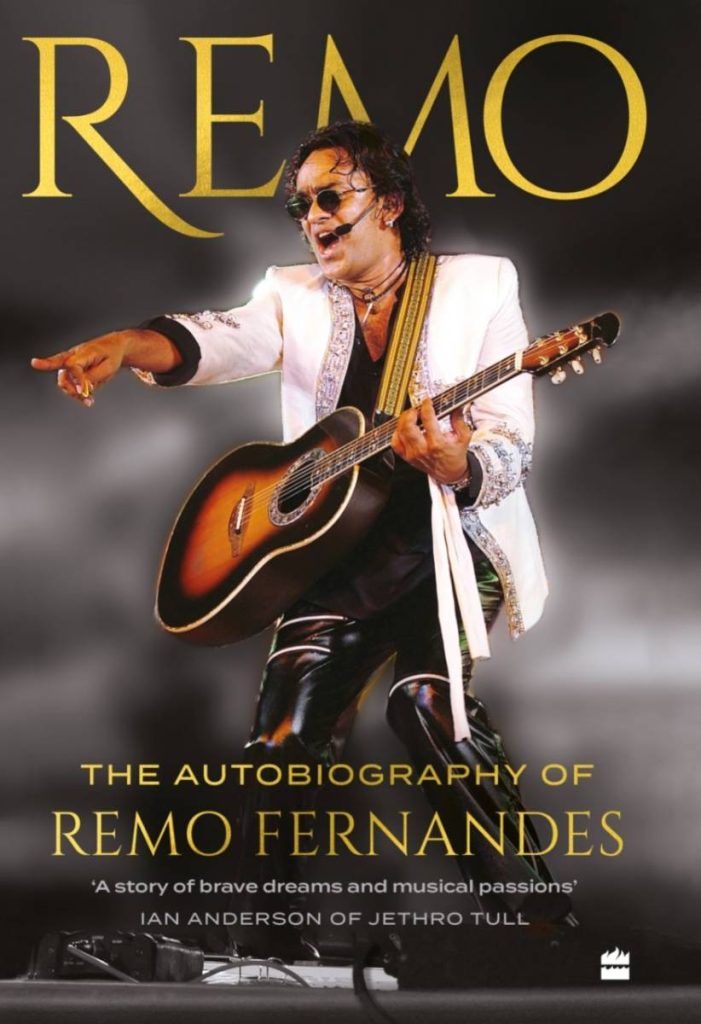

“I neither criticised nor approved of colonisation — I was too young for that — I just accepted it as something that a child would between birth and the age of eight. Today, I see colonisation as a totally illegal and criminal act then perpetrated exclusively by European countries, with blessings and ‘legal’ approvals of their monarchies and their churches,” Fernandes, whose autobiography ‘REMO’ (HarperCollins) has just been released, told in an interview.

“Today colonisation isn’t accepted at all anymore; but countries like the US ‘colonise’ others through different means, mainly financial and political, or through brute military power after fake accusations of ‘possession of weapons of mass destruction’. The worst of human nature will always want to subjugate and exploit other people, animals and even our planet, by whatever means possible,” Fernandes, who currently divides his time between his ancestral home in Siolim (Goa) and Porto (Portugal), added.

He writes in the book that before the Liberation (he was eight then), he was probably not even aware that there was a country called India.

What did it feel like, changing from the Portuguese-influenced Goa to being a part of the Indian Union? Did his parents make any visible adjustments? Were there changes to day-to-day life?

“There were no palpable changes in Goa for at least 10 years after the Portuguese left.

“But personally, as a child, I firstly had to learn this strange new language called English. Portuguese is a Latinate language in which you pretty much pronounce what you write, and write what you pronounce; so it was difficult getting used to useless silent letters like ‘gh’ in words such as light, fight, tight. And this is just one casual example.

“And if we found English tough, Hindi was alien — starting with the alphabets, which were like beautiful graceful designs, but difficult to decipher. Later, I realised that Hindi was even more efficient than Portuguese when it came to writing what one pronounced and vice-versa. In fact, the most efficient I’ve yet come across,” Fernandes explained.

He also had to get used to the tastes of Indian chocolate after the Swiss ones he was used to; to Indian butter after the Danish Blue Peter.

“Indian Amul still didn’t exist then. Now, while in Europe, I yearn for the taste of good old Amul,” he said.

“The upside of the Liberation by India, for a musically minded pre-teen like me, was the introduction of English and American music. Goan, Portuguese and Latin music was beautiful, but rock ‘n’ roll had an excitement of its own. The first rock song I heard, ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and the Comets, is an all-time favourite which I shall always cherish. Eventually, we even learnt how to appreciate some songs from Hindi films and, by the time I was in college, I learnt to appreciate and respect Indian classical music,” Fernandes elaborated.

To what extent has Goan culture influenced his music? Has it impacted the way in which he’s written his autobiography?

“The place you’re born and grow up in always influences you in every way — in thought and in action, and even in your subconscious. Goa is my home, and the Goa of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s is the breast I have suckled on. But as the Mahatma wisely advised, I’ve always tried to keep my home’s windows wide open to the breezes from other places, people and cultures.

“And, if we don’t we keep our minds and hearts dead and shut, we always tend to grow into an amalgamation of every place we have visited, every person we have met, every book we have read, every song we have heard. Even the ones we reject help in our formation, as they provide a reason for that rejection,” Fernandes said.

What are some of the most vivid memories he has from his childhood in Goa?

“Cleanliness in the cities. Unspoilt, lush green nature in the villages. Virginal never-ending beaches with no one but fishermen hauling in their catch of the day, and Goans out on a stroll at the end of a hot summer’s day. Honesty. Warmth. Courtesy. Absence of robbery and crime. Discipline in driving, in observing queues, and in every sphere of life. And love — for each other, and for our beautiful land. Of course there was always petty personal politics, or else Goans wouldn’t have been Goans,” he mused.

Dividing his time between Goa and Portugal, he continues to write songs about Goa, and has extensively written about it in the book. How would he sum up Goa?

“Now I don’t live in Goa exclusively; I divide my time between Porto and Goa. In a way you can say I enjoy ‘the best of both worlds’.

“I remember returning from my very first trip to Europe, which lasted from 1977 to 1979, when I hitchhiked around eight countries in Europe and North Africa during the summers. When I returned, I was on a quest to really discover my Goa; I bought a yellow scooter, and a map which I used mainly to avoid all the roads shown on it — I hit the interior mud tracks.

“Goa was still untouched then, and my drives took me to unexpected friendly villages, lakes and beaches of which only the locals seemed to know the names. I spent the nights in a chapel or temple verandas, and often woke up with a bunch of excited village kids surrounding and eyeing me with curiosity, and I knew just how Gulliver must have felt,” Fernandes said with a smile.

“Today I feel sad to see Goa’s nature and the Goan people’s warmth and honesty corroded and destroyed due to various factors. I do wish our leaders had fought for and obtained Special Status for this rare jewel in India’s crown when they easily could have. Each and every one of them promised it when election time came around. Special Status would have made the exploitation and sale of Goa impossible, and perhaps no one wanted to stop that,” he lamented.

Elaborating on this, he said Porto reminded him of the old Goa.

“Yes, it certainly does. While the rest of India was colonised by the British for about 150 years, Goa was Portuguese for 451 years. That’s a lot of generations. So the Portuguese influence here was much stronger and deeper in all spheres, be it architecture, language, cuisine, dress, thought or music. Therefore, Porto, in fact all of Portugal, reminds of the Goa I grew up in, in some way or the other,” Fernandes said.

What is it like living in his ancestral house?

“It is like literally living in your ancestors’ lap. And my home recording studio, where I have created most of my songs, is in my grandmother’s old bedroom. She was the quintessential grandmother from fairy tales. She had white/silver hair tied in a bun, wore clean starched dresses and Chinese slippers in the house, and always smelled of lavender flowers as she sat me on her lap and told me my favourite story for the thousandth time. I loved her – and she loved me. She always called me her ‘morgado’, or the favourite one. I love to think I have her blessings every time I enter her room,” Fernandes concluded.

ALSO READ-How the world accepted Goa’s Liberation