Works of literature, spanning from the author of the first modern best-seller to a Nobel Literature laureate and more, offer an insightful record of previous manifestations of life-changing epidemics…reports Vikas Datta

An insidious, and unseeable, force is out there, able to strike anyone to cause sickness, and in some cases, death. The only way to stay safe is to keep away from almost everyone else — but that is easier said than done in our urban, inter-connected, and interdependent lives.

There is widespread panic as rumours abound and the crisis brings out the best and worst in people. A description of our Covid-hit world? No, pandemics have hit us earlier too — and are reflected in our literature.

Pandemics/plagues have been regular occurrences across human existence — at the rate of two or three per century, but their dispersal in time and space, their varying impacts, and limitations of memory lead them to be forgotten by future generations. The Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 may be beyond the frame of current human experience, but how many can recall the Asian influenza of 1957 or the swine flu of 2009?

Works of literature, spanning from the author of the first modern best-seller to a Nobel Literature laureate and more, offer an insightful record of previous manifestations of life-changing epidemics.

Let us see some half-a-dozen odd of these, avoiding speculative thrillers about man-made virulent organisms being set loose or the genre where everyone becomes a mutant/zombie, before answering the obvious question: Why should we want to read about something we are now experiencing first-hand with all its attendant sufferings and disruptions?

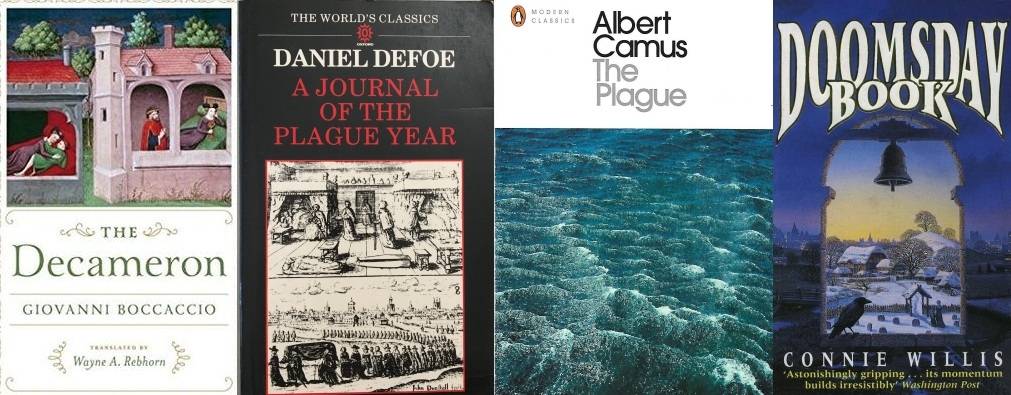

Among the oldest is 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio’s ‘The Decameron’ (c. 1350-53), written as the lethal ‘Black Death”, which devastated Eurasia, was at its peak.

The narrative framework of this collection of 100-odd stories is that ten wealthy young nobles of Florence — seven women and three men — leave the city for a secluded villa in the countryside for two weeks, where they spend all their time telling each other these tales.

While the stories are usually of love — romantic, tragic, and erotic, they also deal with the power of fortune, will, lust, ambition, and of clever repartees, and the characters include generous nobles, lecherous clergy, and travelling merchants.

However, one effort to steal away from the disease that doesn’t go too well can be found in Edgar Allan Poe’s story ‘The Masque of Red Death’ (1845).

First published as “‘The Mask of Red Death’ (1842), it tells how Prince Prospero, ruling over a plague-stricken realm, tries to avoid it by hiding in an abbey, with many other wealthy nobles, Not only that, they also hold a masquerade ball, but amid the revelry, there comes an unbidden guest, and eventually, “… Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all”.

But, the first account of living amid widespread disease is ‘A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations or Memorials, Of the most Remarkable Occurrences, As well Publick as Private, which happened in London During the last Great Visitation In 1665’ (that was how book titles ran in those days), by Daniel Defoe, known better for ‘Robinson Crusoe’.

Presented as an eyewitness account of an anonymous resident, who chooses to stay back in the city, the book published in 1722 gives a vivid description of the sufferings of the residents of London (“A casement violently opened just above my head, and a Woman gave three frightful screeches, then cried ‘Oh! Death, death, death!'”), as the fatalities rise from week to week.

It also analyses how certain groups or individuals fared, the effects on the Church and the government, enlivened with plenty of black humour, verging on the satiric.

Organised chronologically, though without chapters and containing plenty of digressions, it is still systematic and well-researched, leading to literary scholars arguing down the ages whether to treat it as an authentic history or fiction.

Mary Shelley, better known for ‘Frankenstein’, also ushered in the dystopian apocalyptic genre of science fiction with ‘The Last Man’ (1826).

Set in the 21st century, it tells how a plague infects and decimates mankind, and how survivors try to will on to live, while fighting other hostile human settlements.

But with its characters based on her late husband, the poet Shelley, whose biography she was forbidden to write by his family, and friends such as Lord Byron, it also bemoans the failure of their political ideals, as well as the tragedy of human isolation.

While the first modern work on the issue is Jack ‘Call of the Wild’ London’s ‘The Scarlet Plague’ (1912), set in 2073 — some six decades after the eponymous plague has denuded the planet of most of its people and reduced the survivors to a rough existence, which shows how the clock of human progress can be turned back — the definitive work is Albert Camus’ ‘La Peste/The Plague’ (1947).

Set in the then French Algerian town of Oran, it depicts an outbreak of plague, the resulting quarantine, and the response of the varied characters — a doctor, a visiting journalist, a priest, a mysterious visitor, a civic official, and many others — while giving insights into the nature of suffering and powerlessness of individuals to change their destiny in an absurd existence.

At a deeper level, it can be seen as an allegory of the real-life political plague (Nazism) that affected Europe till two years before the publication of the book, but also on Camus’ views about the human condition.

There are many more, across genres. ‘The Andromeda Strain’ (1969), the first book by Michael Crichton under his own name, shows a group of American scientists dealing with a lethal extra-terrestrial micro-organism. Connie Willis in ‘The Doomsday Book’ (1992) brings together time travel and plague and epidemics in the past and the present. And Catherine Ryan Howard’s ’56 Days’ (2021) shows how rather impetuous romantic choices, in the shadow of a pandemic, can have lethal consequences.

But now, to answer why we should read books of this ilk. For one, fiction, for those not totally fixated on TV or web-streaming, offers a way of understanding the scope of the crisis, with stories helping to comprehend something that may seem too huge and frightening to process. Two, it shows that our ancestors also faced such crises, and how they tackled them. And finally,

they provide reassurance that life continues, and it’s up to us to do what we make of it with our choices.

ALSO READ-‘The High Priestess Never Marries’ brings some mystery