As Western fears grow about Xi Jinping’s pathway to militancy and hyper-nationalism, China’s answer is to enact ever-tighter laws to control its people and deter foreign influence. Thus, China amended its Counterespionage Law broadening the definition of espionage and banning the transfer of “national security” information….reports Asian Lite News

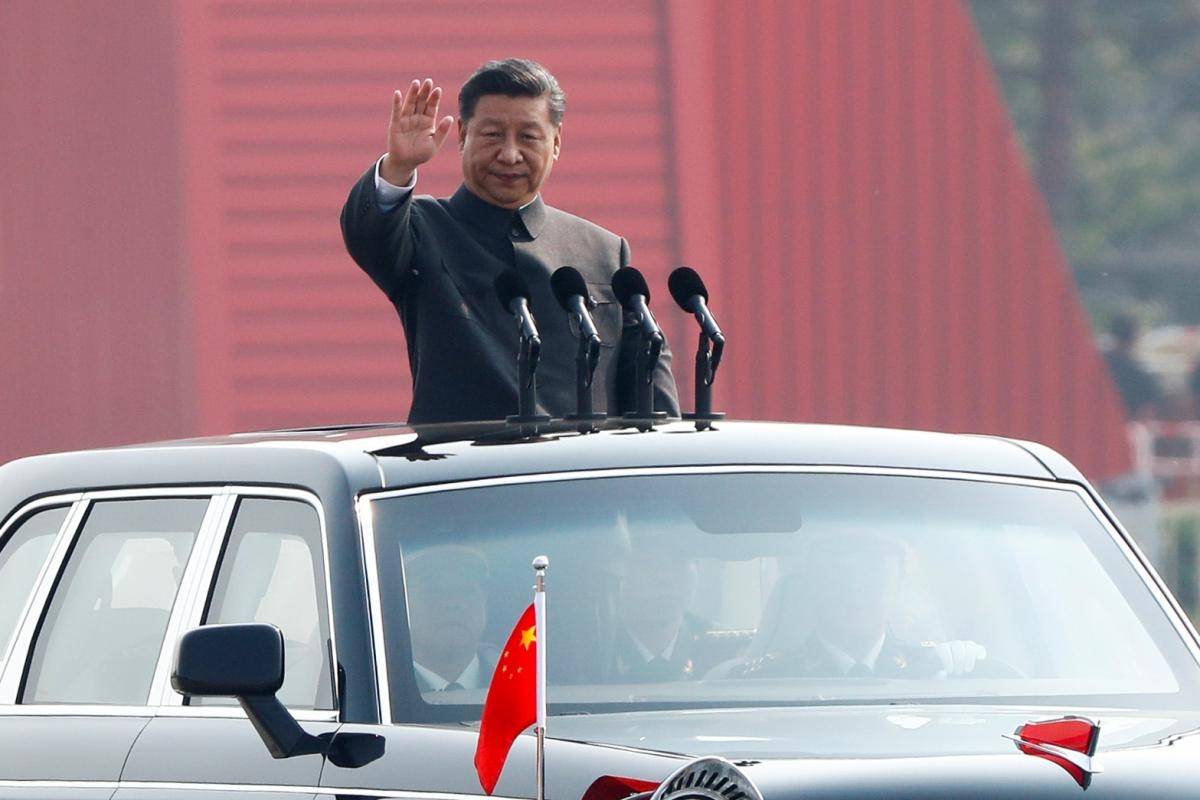

Chairman Xi Jinping possibly thought China would continue its upward trajectory indefinitely. After all, he muses in the socialist ideology that bears his immortal name, the West is in decline and China is on the rise. However, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing all sorts of unexpected setbacks and challenges that threaten to derail its narrative of inevitable pre-eminence.

Even if China continues to push the boundaries of belligerence – with excessive territorial claims in the South China Sea, taunting Japan in the East China Sea, testing Indian limits along their shared border, dispatching high-altitude balloons around the globe to gather intelligence, promoting Russia’s cause against Ukraine, setting up illegal police stations overseas, pressurizing Taiwan with military coercion, and interfering in foreign governments and societies – there is evidence it is resorting to a centuries-old practice of putting up walls to ring fence the Middle Kingdom and keep its inhabitants “safe” from outside influence. As Western fears grow about Chairman Xi Jinping’s pathway to militancy and hyper-nationalism, China’s answer, like that of any communist or totalitarian regime, is to enact ever-tighter laws to control its people and deter foreign influence. Thus, China amended its Counterespionage Law on 1 July, broadening the definition of espionage and banning the transfer of “national security” information.

China’s concept of security comprises 16 broad areas, with political security -maintaining regime stability and CCP supremacy – is the overarching one. Chinese security includes: territorial (protecting borders and territorial integrity); military (defending against military attack, prevailing in conflicts); economic (protect economic stability and development); cultural (preventing harmful ideologies and thinking); societal (maintain public security and societal control); tech (develop science and technology, control new technologies); cybersecurity (maintain information control, defend against cyberattacks); ecological (protect ecosystems); resource (preserve access to natural reserves); nuclear (ensure normal operation and prevent accidents); biosecurity (protects against risks, including epidemics); space (maintain access to outer space); polar (maintain access to polar regions); deep sea (ensure access to the seabed); and security of overseas interests (protect citizens and assets abroad, guarantee access to trade routes).

With such a comprehensive approach, is it possible to contemplate any realm that does not pertain to China’s security?

Foreign journalists working in China, for example, are extremely concerned about the law changes. Newsgathering there could be construed as a violation of the law, such as accessing “documents, data, materials or items related to national security and interests”. As Hong Kong’s experience demonstrates, the beauty of enacting wide-ranging and ambiguous laws is that the government can use them however it wants to stifle dissent.

Mao Ning, the spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, reassured, “There is no need to associate the Counterespionage Law with reporting activities of foreign journalists. China always welcomes media outlets and journalists of all countries to conduct interviews and run stories in China in accordance with laws and regulations.”

Mao noted, “As long as one abides by laws and regulations, there is no need to worry.” Such circular logic assures nobody. These laws are vague, in essence making them incredibly restrictive since they can be interpreted at the whim of the government and its puppet courts. This law was already opaque, and it becomes even more so with the latest amendments. Penalties are harsh, ranging up to life imprisonment or even death sentences.

Reporters Without Borders already ranks China 179th out of 180 countries for press freedom. Only North Korea scores lower. The US National Counterintelligence and Security Center warned that the law gives Beijing “expanded legal grounds for accessing and controlling data held by US firms in China”. This year alone, Chinese agencies have raided the foreign-owned due diligence company Mintz Group and the consulting firm Bain and Company. This whole-of-society approach to national security will affect foreign businesses operating in China, and will also reduce interaction between Chinese citizens and foreigners.

Fewer than 0.05% of residents in China are foreigners. This compares to 2% for South Korea and Japan, both of which are remarkably homogenous populations. By comparison, 7.1% of US residents are non-citizens, and another 6% are naturalized citizens. This pitifully low level of China’s popularity as a place to live is due to bureaucracy, xenophobia and a pervasive security state. Yet Xi does not mind, for his goal is to insulate his nation, to scrub away foreign influences and to mold the populace into pliable putty in his hands.

This amended law is a tweak rather than a course change, although Xi has departed from predecessors by rolling development and security together, rather than chasing merely development.

Last September, the Germany-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) published findings on China’s comprehensive national security policy. It noted, “Xi Jinping has turned national security into a key paradigm that permeates all aspects of China’s governance … This new focus on keeping China safe is driven by perceptions of internal and external threats. It also serves as a strategy to hedge legitimacy risks and ensure continued support for the CCP’s rule as China shifts away from a development-first model.”

MERICS continued: “Xi’s quest for a comprehensive national security formula has reshaped China’s policymaking. The result is a state of hyper-vigilance with wide- reaching effects on state-society relations, China’s economic growth model and how the leadership enforces its interests abroad.”

It also warned that the “securitization of everything” will likely accelerate. “The all- encompassing national security mindset is increasingly locking China into certain modes of action. By priming officials and citizens to be ever alert to potential threats, pragmatism has given way to ideology, heightening the risk of overreaction and arbitrariness. This ‘securitization of everything’ extends beyond Xi’s tenure and will continue to define China’s domestic and international behavior until there is a substantial ideological shift. This new paradigm implies clear – and new – risks and challenges for governments, businesses and non-state actors engaging with China.”

Another new regulation is the Foreign Relations Law, which gives Xi unheralded powers. Beijing can use domestic law to retaliate against foreign sanctions and to deter future provocations. The law, also enacted on 1 July, will punish any entity that acts in a way “detrimental” to Chinese interests.

The Global Times described it as a “key step to enrich the legal toolbox against Western hegemony”. Interpreted, it is yet another instrument of coercion for the Chinese government against any obstacle in its way. It will presumably have the unintended step of causing foreign businesses to reconsider involvement in the Chinese market, as the authorities can raid and investigate their businesses. Xi is surely aware of negative impacts on foreign investment, but his ambition is to shore up his and the CCP’s rule. Any price is worth that, in his calculus.

However, a number of Chinese are increasingly uncomfortable about the direction Xi is taking the country. Last year, some 10,800 high-net-worth individuals (i.e. millionaires and billionaires) departed China for good. This year, the number is forecast to be even higher, with advisory firm Henley & Partners estimating China will lose 13,500 such individuals and with outflows “more damaging than usual”.

The Chinese economy is suffering terribly. Young people are confronting record unemployment in the wake of COVID-19, with little sympathy from the government either. Xi instructed them not to think themselves above doing manual work, moving to the countryside or learning to “eat bitterness”. Indeed, on Youth Day on 4 May, Xi mentioned “eat bitterness” no fewer than five times in a People’s Daily article.

Over the past three years, 54 million jobs were lost in China. Of these, 15 million are college graduates unable to find work, 21 million were laid off by corporations, and eight million were forced out of cities by the pandemic. In 2022, a staggering 10% of Chinese small-to-medium enterprises closed. Meanwhile, the average number of employees at A-share listed companies shrank 11.9% compared to pre-pandemic times. The private sector is the main driver of job growth; last year the government and state-owned enterprises offered just 860,000 jobs, equating to just 5% of fresh graduates.

A record 11.6 million college graduates will enter China’s workforce in 2023. Already, one in five young people are unemployed, and youth unemployment will likely rise by five million annually over the coming five years. This could mean 50 million unemployed youths in China by 2028. This is dangerous for the CCP, for idle and disaffected young people could prove an existential threat.

Dr. Bill Overholt, a senior research fellow at Harvard University, commented: “Now I believe that on its current trajectory China will, by the end of this decade, become the slowest-growing major economy … The geopolitical consequences are vast. The domestic consequences are vast, but unknowable.”

There is great uncertainty for Xi and his undisputed rule. COVID-19, for example, was a black swan event not on Xi’s agenda. This outbreak that brought the globe to a grinding halt originated in Wuhan. Amidst Beijing’s vehement denials of culpability, the CCP made hay with medical diplomacy as it donated personal protective equipment and vaccines.

However, China’s own people finally spontaneously rebelled against the draconian restrictions and lockdowns imposed by Xi. With a snap of the fingers, the Chinese government reversed a years-long policy and let COVID-19 loose on an unprepared population. The world will never know how many died in that sudden plague, but it would have been hundreds of thousands. In a master stroke, the CCP completely undid its narrative that it was all-wise and all-powerful.

Xi and the CCP will double down on ideological indoctrination at home, for this is its only option in the face of growing anger and criticism overseas. This is the oath that the CCP’s nearly 100 million members swear when they join the CCP: “It is my will to join the Communist Party of China, uphold the party’s program, observe the provisions of the Party Constitution, fulfil the obligations of a party member, carry out the party’s decisions, strictly observe party discipline, protect party secrets, be loyal to the party, work hard, fight for communism for the rest of my life, always be prepared to sacrifice my all for the party and the people, and never betray the party.”

Note the repetition of “party, party, party”. In fact, the party appears an astonishing ten times in one sentence, while the “people” are mentioned just once. It is obvious that the “people” do not get a look in in the CCP – it is all about sustaining and advancing the party. It may be technically called the People’s Republic of China, but the harsh reality is that it is the party’s China.

In a candid moment, President Joe Biden recently described Xi as a “dictator”. Beijing may have reacted badly to this, but the label is perfectly accurate. In fact, Article 1 of the Constitution states: “The People’s Republic of China is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants.” Of course, much of this is convoluted, for what is a “democratic dictatorship”? Regardless, the working class certainly does not lead China, for power is instead cultivated, controlled and amassed by party elites.

Another event causing concern for Xi will be tsar Vladimir Putin’s prolonged and unwinnable war in Ukraine. Although it is keeping the USA and NATO occupied, Xi will be ruing how Putin has painted himself into a corner. Score one for the West, and one against authoritarian regimes.

After China’s muted support for Putin during the Wagner revolt, Ryan Hass of the Brookings Institute commented: “There were no visible signs of China rushing to Russia’s defense, and no signals of support from Xi to Russian President Vladimir Putin … Regardless of whether Putin regains tight control of Russia’s levers of ower, Russia clearly is not the strong power that Xi placed a big bet on when Putin visited Beijing in February 2022.”

Hass continued: “No amount of censorship and propaganda will conceal Xi’s strategic misjudgment. To guard against criticism, Beijing likely will assert tighter control over society through surveillance and repression. The CCP will intensify its indoctrination efforts around ‘Xi Jinping thought’. And Beijing will intensify its efforts to limit the emergence of any alternate power centers inside China.”

As is China’s wont for most of its history, Xi is increasingly turning China’s focus inwards. He wants to make the country less dependent on outsiders, to control the people’s thinking, to demand their loyalty and to wean them off foreign influence. Amendments to the Counter espionage Law simply underscore how Emperor Xi is building Great Wall 2.0 around his empire. (ANI)