Swaminathan had the intellectual honesty to recognise the shortcomings of the ‘revolution’ he had spawned along with Dr Norman Borlaugh and speak up for the alternative paradigm of an “evergreen revolution”, which he defined as “improvement of productivity in perpetuity without ecological harm”…writes Sourish Bhattacharya

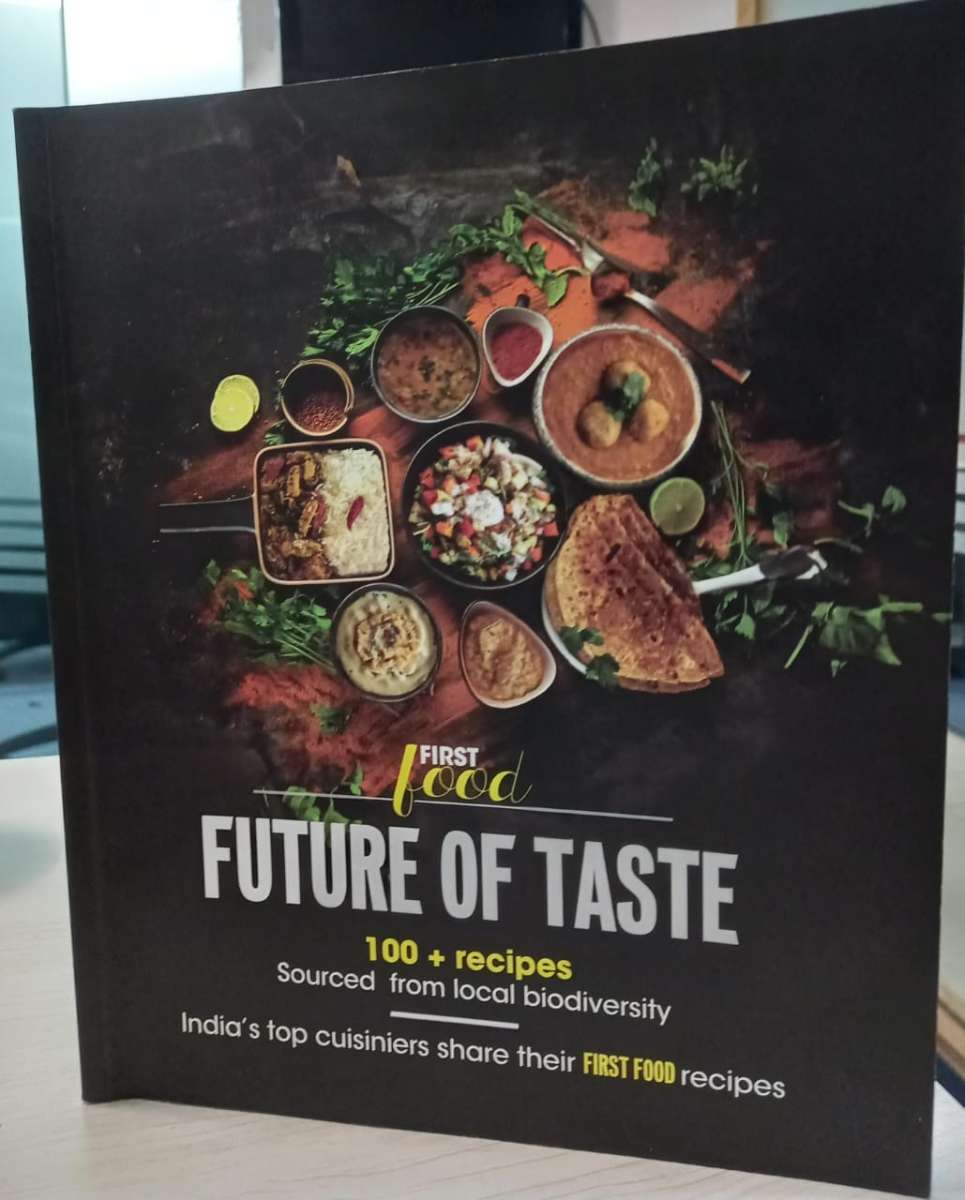

Why does the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), which has been at the forefront of all major debates on the state of our ecosystem since its late founder, Anil Aggarwal, wrote the first ‘Citizens’ Report’ on the State of India’s Environment in 1982, need to bring out a lavishly illustrated book on food and recipes?

Why do we need to know from celebrated chefs how to integrate millets into our daily diet, or why we must reclaim the produce that are fast disappearing from our kitchens — from bathua to chow chow, from meetha karela to tender jackfruit, galgal and jalpai — or make sabzi with guavas and water melon rind, or perk up preparations with wild orange zest, or how to not waste carrot and chickpea leaves, or make pakoras with gulmohar flowers?

Leafing through the fourth book in the ‘First Food’ series conceptualised by journalist Vibha Varshney, this writer could think of many reasons for a book that reminds us constantly that what we eat impacts the life and livelihoods of millions of farmers. Anyone who says food is an indulgence should look beyond the plate to the producer.

Sunita Narain, Agarwal’s acolyte who has kept the torch of the CSE burning brighter since her visionary mentor’s death in 2002, astutely notes in her Foreword to ‘Future of Taste’: “As the world begins to rework the paradigm of agriculture so that it is climate smart, we need to reset [the] connection between food and livelihood, nutrition and nature.”

The volume being reviewed is dedicated to M.S. Swaminathan, the scientist synonymous with the Green Revolution, but criticised later for pushing Indian farmers into the trap of becoming dependent on high-yielding varieties that required soil-destroying chemical fertilisers, poisonous pesticides and huge amounts of water.

Swaminathan had the intellectual honesty to recognise the shortcomings of the ‘revolution’ he had spawned along with Dr Norman Borlaugh and speak up for the alternative paradigm of an “evergreen revolution”, which he defined as “improvement of productivity in perpetuity without ecological harm”.

‘Future of Taste’ brings the “evergreen revolution” to the kitchen by creating awareness about how India’s amazing biodiversity has within it a treasure trove of fruits, vegetables, flowers beans and leaves to ensure variety on our tables and to provide our marginal farmers the means of survival that are getting lost as more and more land is brought under industrial, monovarietal farming of high-yielding, chemical-depending, water-guzzling high yielding varieties.

The central premise of ‘Future of Taste’ is that it is up to us, as consumers, and up to the powers that be to create a vibrant market for sustainable produce. If we turn our back on produce that our mothers and grandmothers welcomed into their kitchens, we will only be compelling farmers to become more dependent on an agricultural system that ends up adding avoidable additives to our malnourished soils and ultimately hurting those who depend on them.

The Narendra Modi government-led celebration of millets, which are best suited to our water-scarce agriculture, underscored the need for initiatives on an all-India scale to integrate ‘Shree Anna’ into programmes such as mid-day meals.

To quote Narain, “… more biodiverse and climate-appropriate millets will be grown by farmers where governments include them in the schemes for mid-day meals … . Change of cropping patterns towards climate resilience will need this supportive structure.” This may lead you to wonder how we — individual consumers — fit into this vast national picture.

Again, Narain provides us a timely reminder: “… the choice of food that farmers grow is in the hands of consumers — us; what we eat and why we eat it. If we change our diets, it provides signals to the farmer to grow differently.”

Setting the tone for the book, Narain adds: “We know that food is medicine, yet we continue to eat … junk. … We are in danger of losing the knowledge of good food — what our mothers and grandmothers cooked in different seasons. This is why we must be part of the changed agriculture story.”

Here’s a recipe book that is in a league of its own — it talks about the challenges confronting farmers, the need for climate-resilient agriculture, the growing negligence of proper nutrition and making good food with unexpected ingredients: all in the same breath. It is a book that must stay with us because it teaches us not only how to cook appropriately based on the principle of eating local, seasonal and nutritious, but also why what we eat makes a real difference to the lives of the millions who work very hard to feed us.