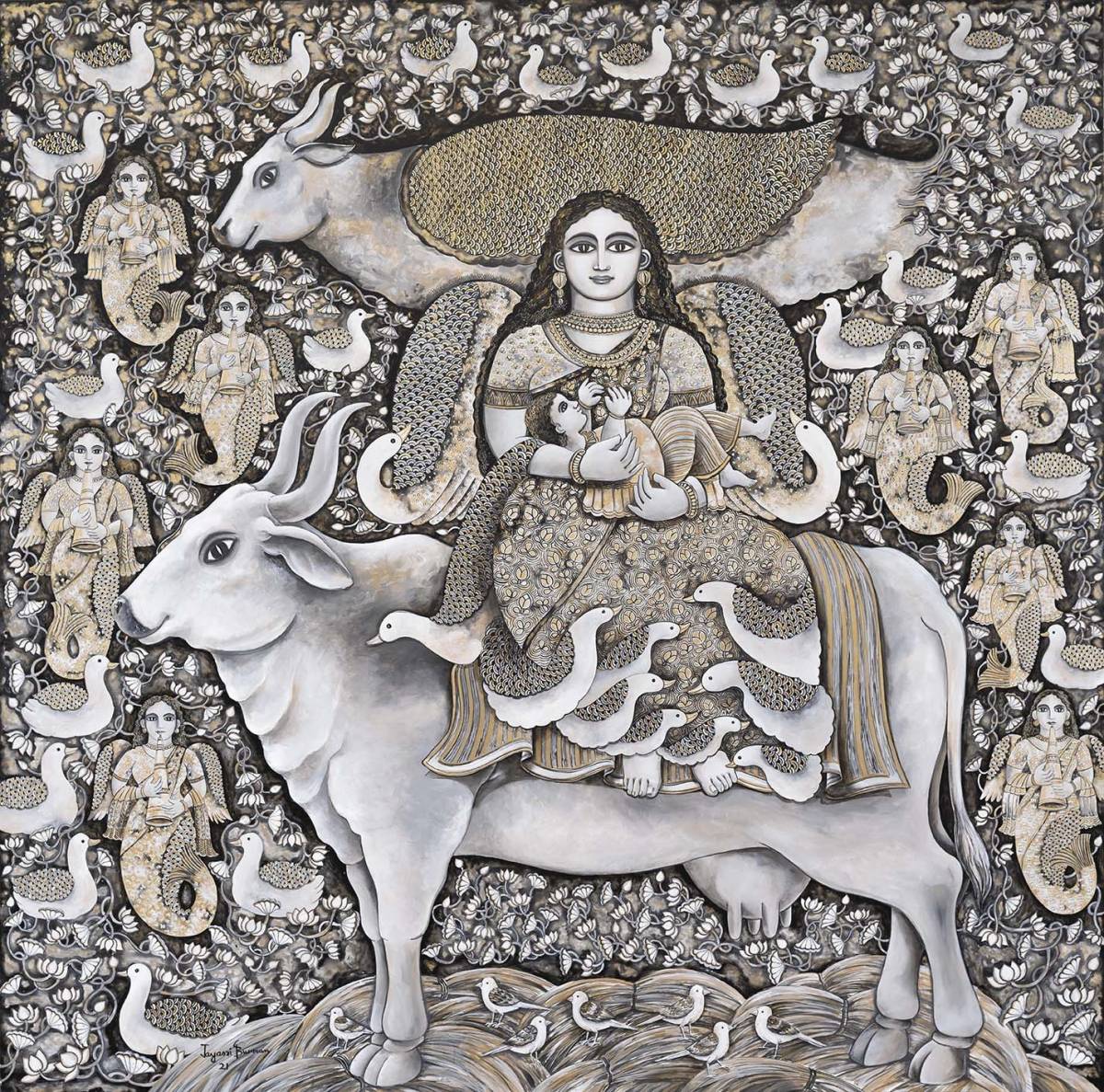

The book is part of a duology on ‘Ila of the Kallady’ lagoon, and is accompanied by a picture book for children, ‘Mermaids in the Moonlight’…reports Asian Lite News

There is a short story ‘Conchology’ in her book ‘The High Priestess Never Marries’, which was the first time she had attempted to bring the mystery of Kallady’s musical lagoon into her work. For author Sharanya Manivannan the tale took years to write as she would keep glimpsing what it was supposed to be, but wasn’t able to gather the complete look until near the end of finishing that manuscript.

“I went to Sri Lanka immediately after the book was published; in fact, ‘The High Priestess Never Marries’ was launched in Colombo first. It was during this trip that something was seeded in my heart about the ‘meen magal’ as a personal and creative motif. A few months later I began returning to Batticaloa, too, where I had only been once before. These trips had as their overt intention researching the meen magal or singing fish phenomenon, but the deeper draw was to be in the place that my family is from, the place I did not get to grow up in or even visit because of the civil war in Sri Lanka,” says the author whose graphic novel ‘Incantations Over Water’ (Westland Publications) that hit the stands recently.

The book is part of a duology on ‘Ila of the Kallady’ lagoon, and is accompanied by a picture book for children, ‘Mermaids in the Moonlight’.

This author of seven books who writes and illustrates fiction, poetry, children’s literature and non-fiction says that she has been drawing and painting since her teens, and writing since she was a child.

“It did not seem unusual to me to bring these two together. It seemed so natural in fact that while I know when I began thinking about mermaids as a creative motif, I don’t know exactly why I chose the visual medium. The mermaids themselves are very visual in Batticaloa, of course: the symbol is across public facades everywhere.”

Recipient of the South Asian Laadli Award for ‘The High Priestess Never Marries’, Manivannan’s books — ‘Mermaids in the Moonlight’ and ‘Incantations Over Water’ were created during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Together, the books form my Ila duology. ‘Moonlight…’ is about a woman from the diaspora taking her child (Nilavoli) to the island and to the lagoon for the first time. During their boat ride, Nilavoli receives an inheritance of stories, which also gently help her to understand her culture and the civil war. The child and mother create a mermaid named Ila, and play with the possibility that she lives in the lagoon. In ‘Incantations.’, it is Ila who is the narrator. As a book for adults, it is a darker and deliberately complex work, going deeper into the region’s realities.”

Adding that when it comes to revealing herself through her characters, it is something that just happens sometimes, and is not really important for her.

“I write and draw primarily for my own solace or pleasure, so anything I feel or think about enters the work.”

Hailing from a country that witnessed one of the longest and bloodiest civil wars in the world, the author feels that it’s vital just not to forget, but also to have nuanced narratives — as well as to understand that the civil war is only over officially, but that scars and tribulations persist in different forms.

“Perhaps I’m aware of the literature and cinema out there because of my personal investment in the topic. Authors like Anuk Arudpragasam, Nayomi Munaweera, Sharmila Seyyid, Rajith Savanadasa, Michael Ondaatje and Shyam Selvadurai have written remarkable texts. One of my favourite novels is Shankari Chandran’s ‘Song Of The Sun God’, which is not about the conflict per se, but Tamil lives over decades. Tamil creatives and activists from India have a long history of appropriating the pain of communities from and of the island, and I would caution against most work by them. Exceptions would be Rohini Mohan, Meera Srinivasan, Swarna Rajagopalan and Samanth Subramanian, who work in different non-fiction disciplines.”

Recalling the emotions she felt while visiting Batticaloa for the first time a decade back, she remembers being ill and sprawled out asleep in one row of the van for 10 hours on the highway from Colombo.

“I can never forget sitting up just in time to see the mermaid arch at the entrance of the town. It was drizzling, and electric lights had been turned on in the late dusk. I saw the mermaid arch — it appears in both the books; it has three mermaids sitting atop it, greeting those who enter or leave the town — and my ancestral temple which is right beside it, for the first time.”

She also recalls that during that trip she sat on the front porch of the house that her grandmother had yearned for deeply and in the final year of her life kept saying that she wanted to see that porch one more time.

“She died without fulfilling that yearning. Still, that trip was difficult for me for various reasons, and I know that the only thing that gave me the courage to attempt to go back there was the pursuit of the mermaids. Being able to tell myself that I was going there out of curiosity about why the mermaid symbol is everywhere in Batticaloa except in the folklore gave me emotional scaffolding for a journey that all and exiles can undertake only at great risk to their hearts. I am profoundly fortunate and grateful — each time I went back, filled my heart, and the overflow of those feelings are what fill my pages.”

Stressing that she thoroughly enjoyed illustrating these books, and this aspect of creating them gave her much peace, the author adds that almost half of the art in ‘Incantations Over Water’ was created during the weeks of her father’s hospitalisation due to Covid-19 during the second wave.

“And in the one month after his demise — my family formally mourned for 31 days, as per Batticaloa customs — the book was finished just before this period ended. Immersing myself in the art buoyed me.”

ALSO READ-Telugu NRIs to Invest In Indian Startups