Xi’s epithet has lost much of its luster, and some Western scholars and commentators now bandy around sarcastic terms such as “Xi’s empire of tedium”, “Xi’s age of stagnation”, “China’s age of counter-reform” and “China’s age of malaise”….reports Asian Lite News

Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing is well used to the growl of armored-vehicle engines, clouds of diesel exhaust and the clanking of tank tracks. On 4 June 1989, it was People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ruthlessly putting down student-led protests, but in more recent times it has been military parades driving past Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders in the Tiananmen Gate seated high above the masses.

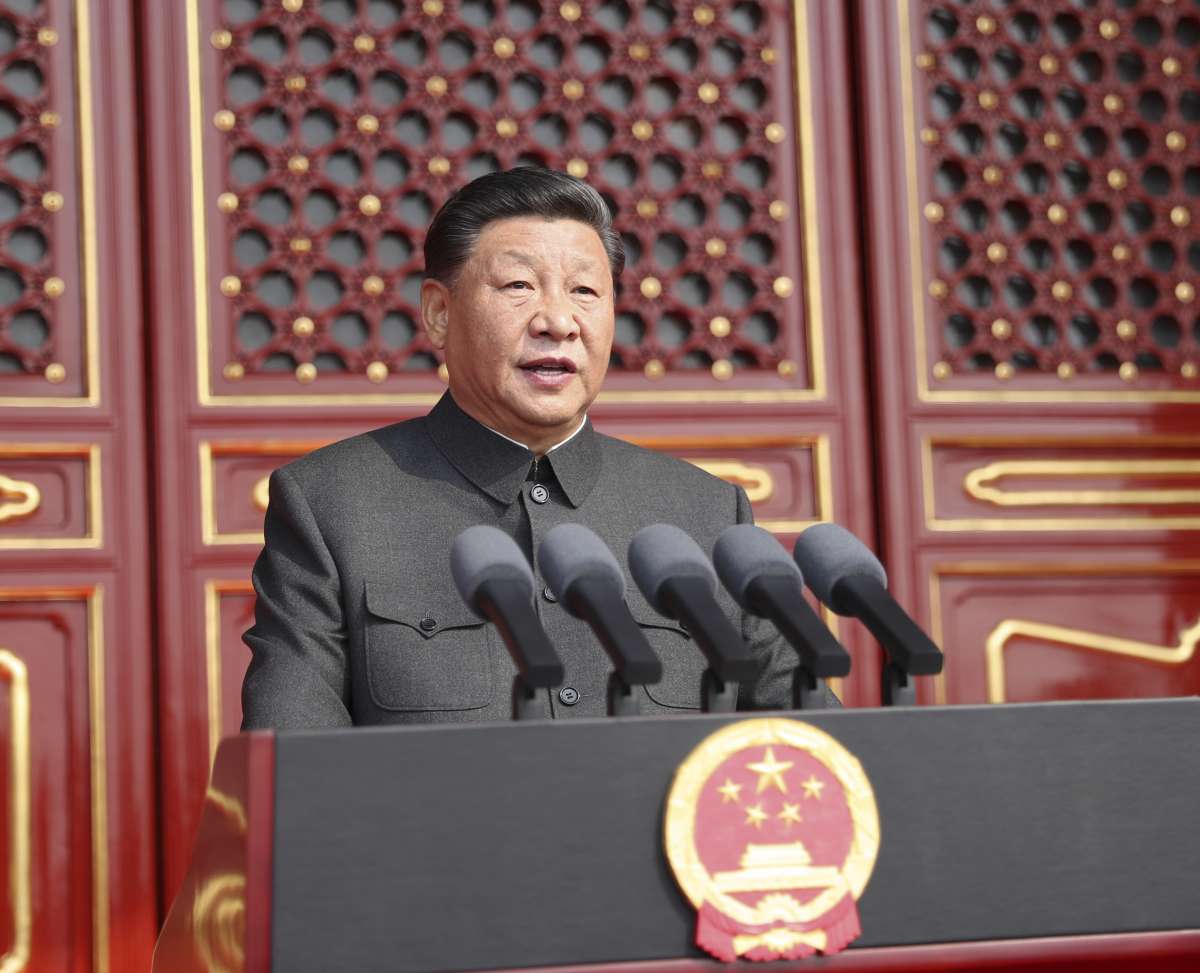

Chairman Xi Jinping and his predecessors typically hold military parades in Tiananmen Square on National Day, 1 October. The last such parade under Xi was on 1 October 2019, plus before that, he hosted one in September 2015 commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

However, on 1 October 2024, activity in central Beijing carried on as usual, with Tiananmen Square merely lined with flower beds and national flags. There was no parade, there was no fanfare, there was no gala atmosphere, there was no assembling of the world’s media to witness the technological and military might of the PLA.

Why not? The Chinese government has been mute on when the next military parade will occur. Certainly, 2024 would have been ideal for a military parade, given that it marks the 75th anniversary of modern China’s founding.

The whole situation is emblematic of the struggle in which Xi and the CCP now find themselves. In 2019 – the time of the last parade – China was enjoying a vigorous golden era under Xi. China’s demigod could do no wrong, the world was bending to his will and China’s future trajectory looked unstoppable.

Yet within just a few months, COVID-19 was spreading inexorably across the globe, economies were shutting down and China itself endured draconian lockdowns. It was a seminal moment for China and Xi, with the emperor shown to be a fallible human. In an embarrassing display of poor planning and cruelty, COVID-19 went from lockdown to rampant contagion across China.

China and Xi have been in recovery mode since then, as the country and party faces ever-stronger international resistance and its own economic woe. China’s dour prospects were apparent in Xi’s speech at a banquet on 30 September, the eve of the republic’s 75th anniversary. The pre-dinner speech was not intended to impart new policies, but it was a useful barometer of the mood within the CCP’s upper echelons.

Xi’s soliloquy contained phrases such as “stormy seas”, “preparing for rainy days” and, following on from the past 75 years, yet more “bitter struggle”.

Arran Hope, Editor of the China Brief at The Jamestown Foundation think-tank in the US, assessed four notable points in Xi’s speech. “First, there was a useful reminder that the CCP sees rapid economic development and long-term social stability as the two main pillars of its legitimacy.” These dual pillars were described as “the two great miracles”.

However, the CCP’s problem lies in the fact that these pillars are showing signs of crumbling. The party has no ready answers for the economic malaise now besetting the national economy, and the only way it knows to maintain stability is implementing evermore repressive regulations on the populace.

Hope continued. “Second was the focus on Chinese-style modernization, which took up a substantial portion of the speech.” Xi said that the central task of the CCP is “comprehensively advancing the building of a strong nation and the rejuvenation of the nation with Chinese-style modernization”. This can only be achieved, according to the CCP, by adhering to the party’s leadership. The only “solution” the party can offer is blind obedience to Xi, closing ranks and fighting on through the pain and suffering. Xi can only demand greater loyalty and commitment from the people. He has decried Western-style democracy and advocated a Chinese model – there is no turning aside from this pathway created by the CCP. To do otherwise, to reverse course, would be an admission of fallibility and thus a loss of legitimacy.

Thirdly, Hope pointed out, “Another prominent feature of the speech was the space dedicated to Taiwan. Taiwan is traditionally mentioned in the PRC’s National Day speeches, as it remains central to the country’s conception of itself. This year, however, a whole paragraph – nearly 10% of the entire speech – was dedicated to the topic.”

Xi made no references to peaceful cross-strait ties. Instead, Xi took a hardline and emphasized the blood ties between the mainland and Taiwan, the latter described as “sacred territory” belonging to China. He also claimed reunification was inevitable, since “the wheel of history cannot be stopped by anyone”.

As a step on its historic mission to claim Taiwan for the CCP, the PLA commenced its one-day-long Joint Sword-2024B military sea and air wargames around Taiwan on 14 October. The People’s Daily said the PLA was “compelled” to conduct these drills because President Lai Ching-te had declined China’s “olive branch”.

However, nobody has seen or heard of China’s olive branch; indeed, Beijing has done nothing but crank up military coercion and diplomatic pressure on Taiwan. Rather than offering an olive branch, China is wielding a big stick to show its strength. In reality, it makes no difference what Taipei does or does not do – China will continue to escalate no matter what.

Taipei responded to the Joint Sword-2024B exercise with the following criticism: “PLA Eastern Theater Command has announced joint military exercises in the surrounding waters and airspace near Taiwan. ROC Armed Forces strongly condemn the PLA’s irrational and provocative actions and will deploy appropriate forces to respond and defend our national sovereignty.”

Returning to Xi’s speech, “The final notable part of the speech, coming shortly before the toast, was an invocation to prepare for ‘unpredictable risks and challenges’. Warning that the country ‘must be prepared for danger in times of peace’ is not a triumphalist way to close out a speech, and suggests a lack of confidence among the leadership. It perhaps goes some way to explain why the events that marked National Day itself were muted.”

Symbolic dates and anniversaries are extremely important to the CCP, so a 75th anniversary should have been marked by great festivity. There were no grand festivities, but only various banquets and concerts, probably because the CCP did not want to antagonize people with overt symbols of triumphalism. Such displays would have been impolitic given the financial crisis that many Chinese now face.

Hope also compared Xi’s latest speech with the one that Jiang Zemin gave in 1999, on the occasion of modern China’s 50th anniversary. “Convictions of the historical inevitability of the PRC’s rise feature in both, as does the certainty that socialism is the only correct model for the country to follow. While many of the specific rhetorical constructs of the Xi era are missing from the earlier speech, Xi echoes Jiang in allying the PRC with the countries of the Global South.”

The Jamestown Foundation editor added that the “the core substance and direction remain the same. Namely, the desire to diminish the influence of the West in the world and promote the PRC’s preferences in its place.” Interestingly, Jiang’s most prominent phrase was “a brand-new era” for the Chinese nation, whereas Xi routinely refers to the “new era”.

The “new era” was incorporated into the CCP constitution in 2017, and it reflects an assessment that the world has entered a period in which the global balance of power has shifted in China’s favor. However, Xi’s epithet has lost much of its luster, and some Western scholars and commentators now bandy around sarcastic terms such as “Xi’s empire of tedium”, “Xi’s age of stagnation”, “China’s age of counter-reform” and “China’s age of malaise”.

It is not only Westerners who have provided such critical labels. Last year, essayist Hu Wenhui described China’s current period as the “garbage time of history”. Some are even going so far as to suggest that an end is in sight. In fact, while Xi may refer to “the wheel of history”, some see history repeating itself as modern China might mirror the collapse of the Ming Dynasty in 1644.

Russia was the first nation to establish a “new era” partnership with China, this occurring in June 2019. It encompasses a strong sense of alignment with China’s strategic vision and how it is challenging the global status quo. This ideological agreement is critical to Sino-Russian relations, as they oppose so-called US hegemony over the global order.

There are numerous levels and a hierarchy in China’s use of partnerships, even if it never delineates precisely what each label means. The most common are “cooperative”, “strategic” and “comprehensive”. In fact, China uses 42 unique adjectival combinations for the quality of partnerships, which suggests they are tailormade for each occasion. The UK alone, for instance, has a “global comprehensive strategic partnership for the 21st century” with China.

Very weighty are the partnership terms “all-weather” (initially used for China’s relationship with Pakistan, but later extended to Belarus, Venezuela, Ethiopia, Uzbekistan, Hungary and all of Africa) and “permanent”, with Kazakhstan enjoying the latter status.

Last month, Beijing elevated the diplomatic status of no fewer than 30 African countries. This means that every African nation – except for Eswatini, which maintains diplomatic relations with Taiwan – now has at least a “strategic partnership” with China.

As the analyst Jacob Mardell explained in another article published by The Jamestown Foundation, “‘Partnership diplomacy’ plays a central role in PRC foreign policy. Through its partnership network, Beijing seeks to shore up global support by swelling its ranks of various types of partners. There are no direct economic or institutional implications to becoming a ‘strategic partner’ of the PRC, nor are there necessarily material benefits to advancing to the level of ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’. Such promotions can be significant in other ways, however. For partner countries, being officially designated a close partner can provide opportunity for real cooperation.”

Whereas the US values alliances based on mutual values, China pursues a different approach. Notably, China prefers partners rather than allies, meaning it can reap benefits from friendly economic cooperation but avoid any diplomatic entanglements. China’s partnership diplomacy gained momentum in the 1990s, and its very first strategic partner was Brazil.

Mardell noted: “This narrative is a core part of the PRC’s value proposition to the Global South. Beijing seeks a values-agnostic ‘democratization of the international order’ and proposes the creation of a harmonious ‘global community of common destiny’. These CCP concepts increasingly have been inserted into partnership statements in recent years. This helps build support for Beijing’s global leadership and its vision for a new international order.”

China has perhaps one ally, though. In 1961 it signed a mutual defense treaty with North Korea, although it has never been invoked. In the Korean War, North Korea invaded its neighbour, China provided soldiers and Russia handed over arms. Approximately 70 years later, in a kind of reshuffle involving the same “partners”, Russia invaded neighbouring Ukraine, North Korea is providing arms and people, and China is supporting Moscow’s military industrial base and Russian economy. Perhaps not much has really changed between the alignment of these three partners against the West and democracies.

Hope concluded: “As the PRC reaches its milestone 75th anniversary, the health of its body politic has come under scrutiny. Official rhetoric from the party continues to tell a good story, but as Xi Jinping’s speech makes clear the positive energy of the propaganda messaging is shot through with concerns about the path forward and the risks and challenges that lie ahead. Those darker undercurrents are reflected in the characterizations of the PRC’s predicament articulated by many alternative voices, both inside and outside the country.”

Whichever one way looks at it – whether from the perspective of China’s ruling party or the people – most agree there was little cause for celebration on this year’s National Day. (ANI)

ALSO READ: China starts new round of war games around Taiwan