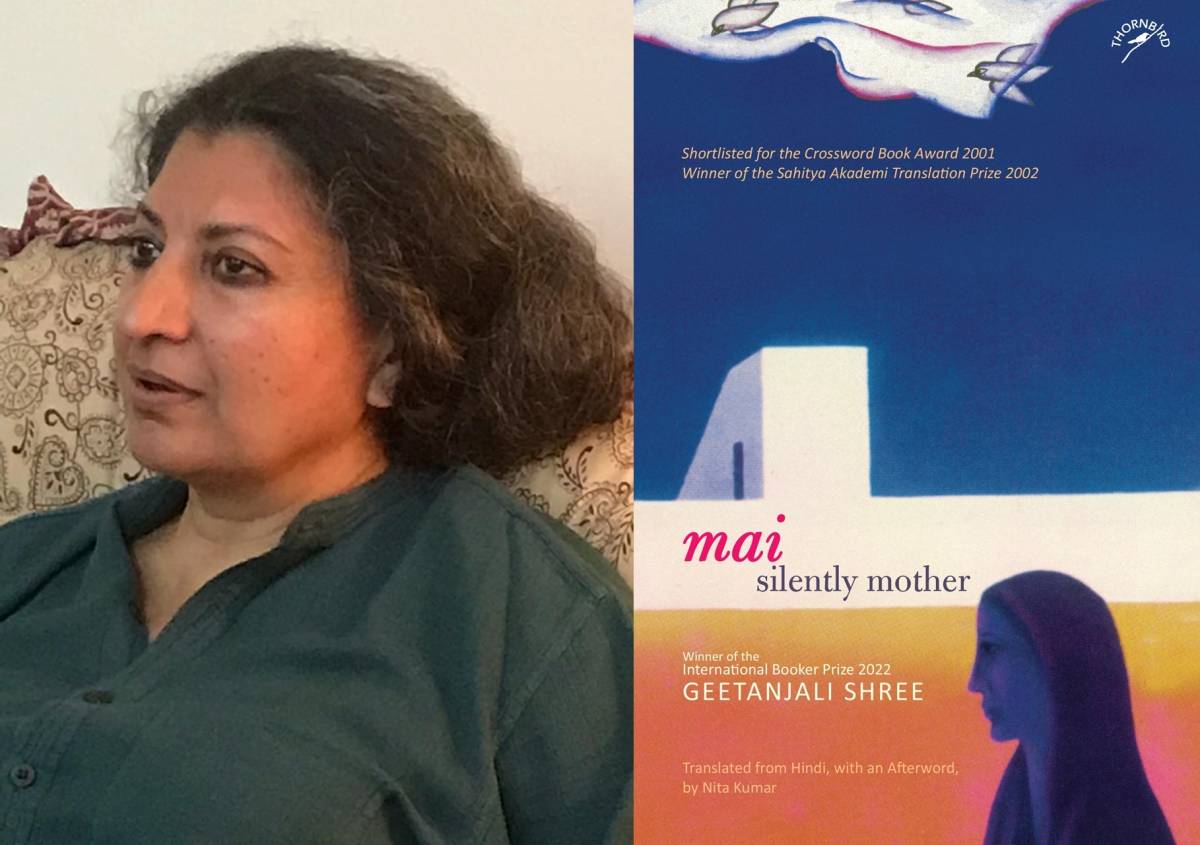

The Booker she won for the novel translated into English by Daisy Rockwell revolves around an elderly woman confronting depression who decides to visit Pakistan after several years of the partition has not only illuminated her work but also brought into focus the entire South Asian region…writes Sukant Deepak

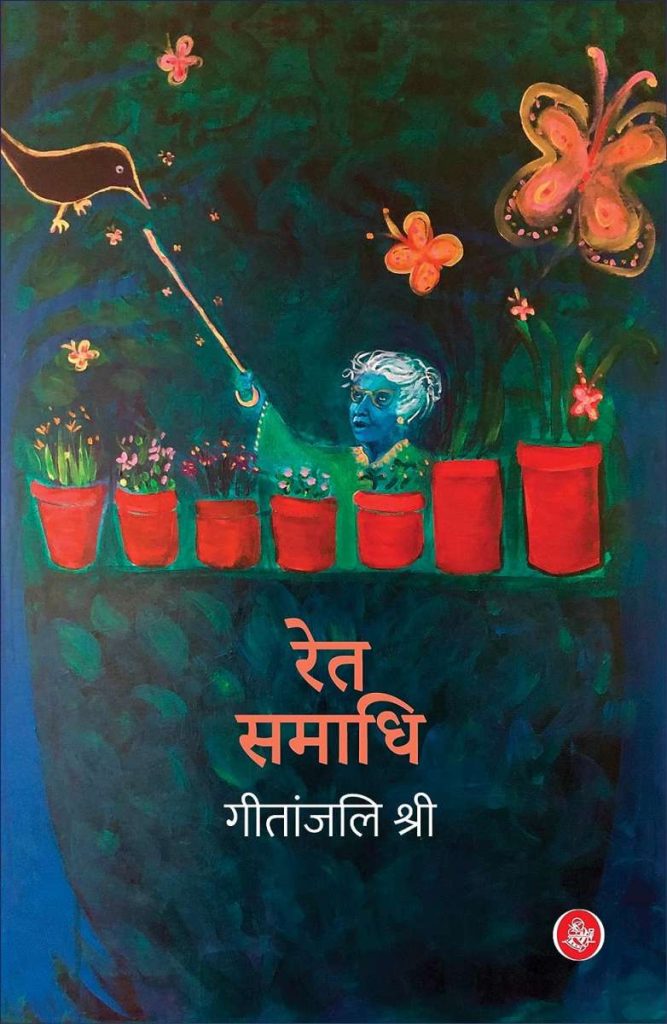

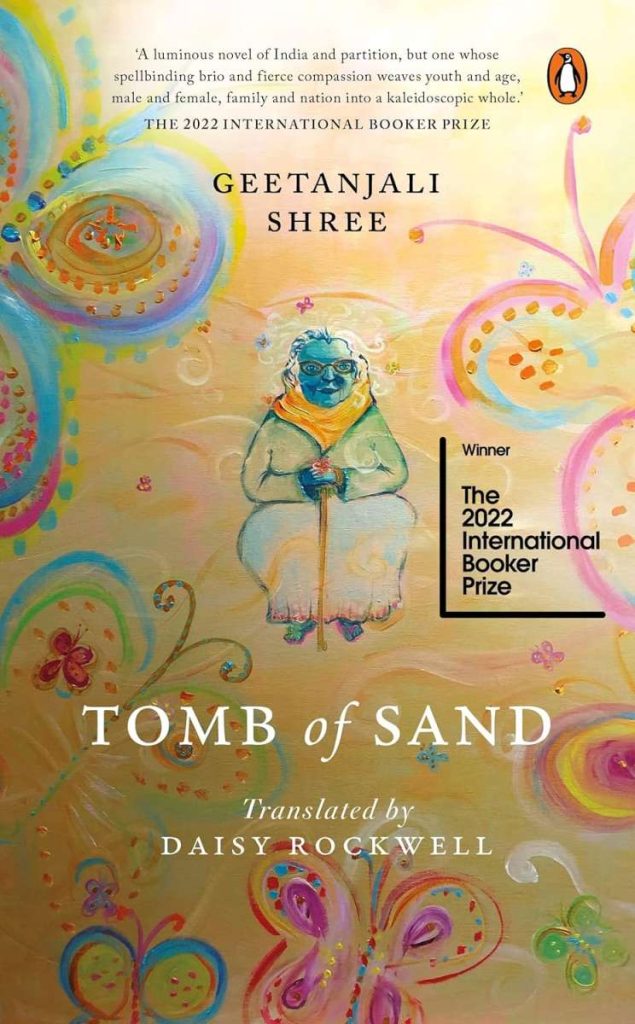

Even as she gives final edits to her upcoming novel titled ‘Sah-sa’, Geetanjali Shree, International Booker Prize winner (2022) for ‘Ret Samadhi’, translated as ‘Tombs of Sand’, for who the last year has been about attending multiple literature festivals, book launches and giving talks; says a writer’s life is always about striking the desired balance between how much to be in the midst of everything and how much to go into retreat and solitude to mull over things and create.

Adding that Booker has brought home that negotiation in a very dramatic and intense way, and overnight, she stresses that currently she is catapulted by it into a very public space, of much visibility and audibility, which is daunting for a person with the opposite leanings that she is.

“It is also rattling to be seen as an expert of well-nigh anything and answer questions about any and everything. Even more traumatic if you will, is the aggravated embroilment with forces such as the market, advertising, and selling. The final edits of ‘Sah-sa’, need a concentrated slot of time, which I am not able to get, so it is happening spread out over several slots of time,” she tells.

Shree also feels that on the converse side, Booker has ‘returned’ literature to her.

Stressing that it came soon after the world started to open post-pandemic, the author says, “The latter had turned the future into a big gloomy question and writing too despaired, though it carried on because while you are alive you breathe! But suddenly – overnight, as I said – I was back in the world of readers, writers, and books, with a vengeance. It has been overwhelming to connect with so many more of my community and my love. Of course, I need my writer’s space back. I am slowly getting it back…”

The Booker she won for the novel translated into English by Daisy Rockwell revolves around an elderly woman confronting depression who decides to visit Pakistan after several years of the partition has not only illuminated her work but also brought into focus the entire South Asian region.

Shree says, “How can I feel anything but good about it? After all, however much of a loner one might be, we all represent more than just our own single self. I carry my community, my world, my times, and society in me, and in a mysterious symbiotic umbilical cord link, we are made of whispers and echoes of each other. I am happy that through me, the light is shed on a larger world around me – it is my moment but also a collective one.”

Mention the fact that the entire conversation is around ‘Ret Samadhi’ only, and a lot of her other important work (including ‘Khali Jagah’, ‘Hamara Shehar Us Baras’, ‘Tirohit’ and ‘Yahan Hathi Rahate The’) not getting the attention they deserve, and she asserts, “What is the attention one deserves? Who gets it? A mishmash of things, especially in today’s world of hype and market, affects that. I have never been the sort of writer who stresses about how much or how little attention I am receiving. Readers must reach out and search out books, I am hardly going to spend my time beckoning them! Yes, ‘Ret Samadhi’ is in focus because Booker pointed that way. Serious readers know an award is recognition but does not ‘birth’ the author. I like to believe they are interested in the writer’s entire oeuvre. ‘Ret Samadhi’ is enjoying its ‘moment’. Lovers of literature will explore further, or else…their loss …!”

For someone who prefers to stay away from social media, a space now being used quite aggressively by many writers and artists, Shree feels that the medium is a mixed blessing — It has worked well for quick communication and relaying of ideas, and debates, but on the converse side also led to wile conversations and rumour-mongering.

“It has also often dumbed down debate and arrogated to itself the presumption that it is a reliable judge of quality and will make and break reputations. I prefer to keep far from it, much as I keep away from ‘market’ considerations as a guide to my writing life. Marketing is not of primacy to me and certainly not what I wish to expend my energies on.

“Of course, I am a creature of my times, caught in the winds that blow. So I cannot claim that market forces do not touch me, but I just do not concern myself with them. What happens and does not happen there is a dynamic of things not of my will or desire. I prefer it that way. The writer and her work belong to her time but – people aggressively in a market rat race forget this – importantly, also to a space and time that is beyond today and which is where Literature revels and resides. We can only do what we are doing sincerely and time and space will give us a slot. Or not,” she adds.

However, she does say that encounters with readers can be most life-affirming for a writer. Citing an example of an emotional son who approached her during a literature festival and said her book was the last book his mother read, and after reading it she folded her hands together – he repeated her gesture. “I cannot exactly replicate it – and she said to him that she wants to meet this writer. It was sad and joyous to connect with her son and feel her humanity, appreciation, and presence. It certainly makes you grateful for the community you belong to and humbles you ‘proudly’ for a small joy you have been able to give.”

Even as debates rage on the role of a writer/artist about recording political and social scenarios of their times, and the observation that the divisiveness of Partition is not just a thing of the past, she believes that recording stories, all stories, is important, and they don’t just belong to the present, but also to the past and the future that we imagine, want or fear.

“But it may not be a conscious agenda of the writer to record something. Rather her sensitivity, which hones her observation and intuition, takes her naturally along that way. Partition is a reality in North India. It continues to ramify into new and undesirable effects. I do not have to try to write about it. It is in my and our being. But partition is also a universal human experience and mostly a painful one. From which emanate innumerable stories which will continue to be told in all parts of the world,” says Shree, who was recently in Chandigarh for ‘Literati’.

The writer, who believes in ‘discovering’ the stories already fluttering inside her or in those around, intuition plays a huge role. However, she believes in intuition, not as some glorified super-human place, but rather a source in us, which is refined as we go along – by our locations of all kinds be it history, geography, autobiography, biographies, sensitivities, observations, imagination, aesthetic sense, even chance.

“I can hardly make an expert exhaustive list! I often quote Ustad Ali Akbar Khan on this – that when he starts he plays the sarod and soon the latter takes over and plays him. That is the beauty of artistic creation. Also, some of our deepest possibilities, both good and bad, lie in our subconscious, our entrails, if you will. A writer takes courage to discover those lights and darknesses, both.

“One is, of course, surprised at various points in the creative process – where did that come from? But that is precisely where that undefinable energy or breath lies, which enlivens a work of art,” she says.

While the past decade has seen a major rise in translations from Hindi and other languages into English, and there may also be fears of something being ‘lost’ in the process, she feels there is a need for translations among other languages.

“The hierarchy with English on the top is limiting and has mono-language repercussions, which feeds into all kinds of monocultural impulses. And that monocultural impulses make easy link-ups with dictatorial ambitions. Besides, there is such a rich conversation out there for humanity in celebrating the plurality of languages as language comes with its culture and philosophy, and the vocabulary of seeing, being, and expressing gets extended for all. The writer and the translator are matchingly important; mutually so, too. One facilitates the other and also extends the other.

“Something is always lost in translation. But let me hasten to add that everything is translation starting from rendering an inchoate, inarticulate thought/feeling into words. Just shifting from one set of expressions to another is translation and that is a process, not a complete exercise. So something constantly changes, but also opens another world. ‘Lost’ must not be seen as a negative here. Perhaps changed is a better word. Translation – approximating towards – that is exciting, enriching, ongoing, evocative. No closure here.

“Most importantly, translation is not about moving technically from some exact meaning to the same meaning – replicas are not being sought or possible, except by machines, and maybe not even there. The endeavour is to carry across a feel, an experience, a sensibility and sensitivity, a cadence, a philosophy, and it acquires a new dimension as soon as it is uttered in another language. ‘Pyar’ and love echo their own separate worlds. So translation is the same and also always different and it is an energy that does not end. This inconquerability, uncontrollability, has to be enjoyed for it’s all about the ephemerality, changeability, malleability, volatility, and fluidity of experience. Translation is life, not death,” she concludes.

ALSO READ-Booker list helps me develop faith about view of life