Prakash Mishra, a local journalist involved in the campaign, remembers how the hills were left with just tree stumps when industrialisation triggered deforestation in Bokaro…reports Rahul Singh

Tribal activist Yogo Purti’s face lights up every time he surveys Satanpur hill, located behind his modest dwelling at Jaipal Nagar in Sector 12 of Bokaro district in Jharkhand.

The 47-year-old, who runs the Asas School that offers free classes to the underprivileged, has fought off threats from the land mafia, the mistrust of villagers and official inertia in Jharkhand to restore greenery on what was just a denuded landscape in his teens.

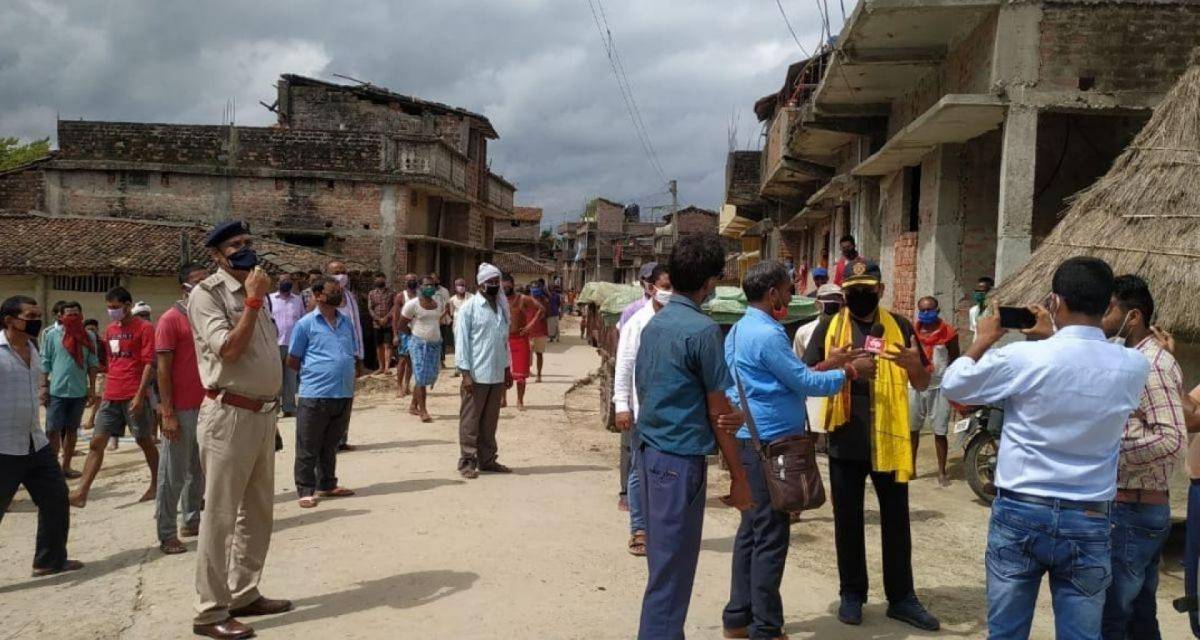

Purti’s environmental activism took shape in 2000, when he successfully mobilised the youth of Satanpur panchayat for a sapling plantation drive on the Satanpur and Bandhgora hills, adjacent to the district’s Chas block, known for its steel plant. With time, the villagers began to watch out for encroachments funnelled by real estate and land mafias and passed on the gathered information to the district administration and the forest and police departments.

The system worked well to stop encroachers in their tracks, and with it, sakhua, khair, jamun, palash and other varieties of trees bloomed and spread shade. The water level increased and much of the wildlife and birds that hadn’t been seen here since before the 80s were thriving once again.

Along with Ramkumar Manjhi, Ramdayal Singh, Shyam Lal Bauri, Ruplal Manjhi and Shrinath Marandi, Purti and the other villagers thus transformed the hills into a buffer zone to protect their habitat from the onslaught of urbanisation.

“Many low-altitude hills around this place were levelled and sold. These two survived only due to our spirited involvement and vigil. We used to organise van mahotsavs to plant saplings at the foot of the hills. At times, rallies were held to spread awareness about tree conservation. We also bonded over freshly-prepared khichdi served on the occasion.”

Prakash Mishra, a local journalist involved in the campaign, remembers how the hills were left with just tree stumps when industrialisation triggered deforestation in Bokaro.

“Alarmed by the sheer volume of environmental damage, we held a meeting with the villagers and decided enough is enough. With our sustained care, the stumps grew back to life. We planted more saplings at the foot of the hills, too,” he added.

The local residents here understand that a thriving hill means a thriving life. They have witnessed how thousands of villages in the state migrated due to rampant mineral ore mining in the region.

The real breakthrough, however, came in 2006, when the then Dhanbad divisional forest officer (DFO), Sanjeev Kumar, organised a meeting with the villagers of Satanpur. He played a pivotal role in constituting forest defence committees, which would go on to look out for encroachments and inform the departments concerned to prompt swift action. Simultaneously, Purti received support from an NGO, Sahyogini, for the plantation drive.

The lands around the hills – the Garga, a tributary of the Damodar river, flows adjacent – were originally occupied by peasants. They were part of the swathes acquired and transferred to Bokaro Steel Limited (BSL) for building the plant. Additionally, forest lands were given to BSL – incorporated as a limited company first and later merged with the Steel Authority of India – to conduct a massive afforestation drive. However, BSL did not utilise the land as required and encroachments soared.

The sticking points

Over the years, several colonies emerged around the Satanpur and Bandhgora hills. Purti and his team alleged that the adjacent plots fell into the wrong hands, who then fabricated documents by posing as peasants. The encroachers later sold them to builders. During his tour of the area, this correspondent also noticed rapid construction and levelling of land.

According to activists, the presence of colonies has heightened the risk of encroachment on the hills. They cited an incident from August 2014, wherein the forest department booked four office-bearers of Adarsh Cooperative Society, one of the many builders around the region, on charges of clearing two acres on Satanpur hill.

A forest officer who retired from Bokaro division last year said, on condition of anonymity, that the hill was given to BSL decades ago.

“Our department had made repeated correspondence with the public sector enterprise during my tenure to get the land back, but in vain,” he added.

On the issue, BSL Communication Officer Manikant Dhan claimed he was “not aware of the Satanpur hill land being under BSL’s control”. However, he did accept that many colonies had cropped up in the area.

Forest Range Officer Niranjan Tiwari said that only the DFO could provide information on the subject. When this correspondent managed to reach Bokaro DFO AK Singh after several attempts, they were officially asked to file a Right to Information (RTI) request with his queries.

On the other hand, Bandhgora’s ownership status is as clear as can be. A few years ago, Purti had filed an RTI application with the Bokaro divisional forest office in this regard. The reply clarified that the forest department fully owned the hill, citing the plot number and details of the entire forest area in the township.

The activist further said that the administration had taken action several times on the complaints local residents raised, but they still have to constantly write to the departments concerned, file RTI pleas and create awareness to save the hills. After he once wrote to the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, it directed Jharkhand’s Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF), in August 2015, to stop the felling of trees and illegal encroachments.

The environmentalists find solace in the fact that one portion of Satanpur’s greenery is protected by the presence of the Jharkhand Armed Police’s firing range. Set up almost 15 years ago at the foot of the hill, it significantly helped curb encroachments on that side, besides preventing the extraction of murram soil used for filling land during construction work.

Testing times

“We saved both the hills by preventing forest erosion and encroachments, but our forest defence committees have been dormant for four to five years,” rued Ramkumar Manjhi, a member of Purti’s green brigade from Santaldih. “Real estate and land mafias lure residents to clear forests on their behalf, which is more difficult for us to stop as it leads to fights in the village and creates personal enmity.”

Ramdayal Singh, who contested the recent election to head Satanpur panchayat, nodded in approval: “These local agents hamper our work.”

Purti and Manjhi claimed that the committees became inactive primarily due to the issue of local agents. Department-level negligence, too, has affected them, especially as forest officers play key roles in their formation and operation.

Sanjeev Kumar, who is still remembered by the villagers for his unflinching support for their campaign, is now the additional PCCF of the forest department’s CAMPA Project.

“When I convened the meeting to form forest defence committees, we vowed to ensure that it wouldn’t die out as a one-time programme. Instead, it should set an example for others,” Kumar said.

Unfortunately, only the group led by Purti and team is presently active – basically on their own terms – and land mafias are not pleased. Yet, they yearn to persist to keep the villages green and sustainable.

ALSO READ-Sanskruti-Veekshanam amazes audiences at Nehru Centre